August 12, 2018 – Washington, DC, Unite the Right 2 Counter Protests at the White House. Photo: Melany Rochester

By Chrystie Flournoy Swiney | April 2, 2019

Democracy seemed ascendant after the rivalry between communist and democratic states subsided in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. As elected governments replaced many toppled totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, the number of democracies rose.

Yet with rare exceptions, authoritarian leadership and other undemocratic governments have been the norm throughout human history. So perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that democracy seems to be losing ground after its post-1991 surge. The rise of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Donald Trump in the U.S. are among the most visible examples.

As a human rights attorney completing my Ph.D. in international relations, I’m researching why democracy appears to be declining around the globe. In addition to the growing number of far-right, authoritarian-leaning leaders who certainly bear responsibility, lawmakers in historically strong democracies are proposing and passing legislation that adds new layers of red tape, restricts access to foreign financial support, and makes it harder and riskier to engage in peaceful protests.

From India to Poland to Israel, legislators are limiting the freedom of independent nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations. Many of these groups are responsible for holding governments to account, standing up for minority rights and providing services to the indigent, among other critical roles.

New restrictions

My research focuses on the spread of undemocratic civil society laws in historically democratic states. These laws include bills that impose new restrictions on forming, operating and funding civil society organizations. They are limiting the activities of charities, watchdog organizations, protest movements and nonprofit service providers, such as health care clinics depended on by people lacking access to affordable health care.

For nearly a decade I’ve tracked and documented the spread of these laws. By my count, at least 58 percent of the world’s strongest democracies have adopted at least one restrictive civil society law since 1990. Counting proposed laws, another 5 percent are in this growing category.

I’m not talking about similar legislation passed in non-democratic and weakly democratic states like Russia, Egypt and Turkey. These laws are also problematic and troublesome for global civil society, but are not the primary focus of my research.

Consider what happened after Russia enacted a law in 2012 that requires all nonprofits wishing to receive any amount of foreign donations and that are engaged in what the government defines as political activities to register as “foreign agents” – a toxic term in the Russian context.

Since then, elected politicians have passed measures with similar objectives in countries with democratic governments, including Israel, India, Austria, Hungary and Poland.

In trouble

Democracy experts like the independent watchdog Freedom House generally agree that democracy is in trouble around the world. They no longer debate whether democracy is imperiled, but by how much and whether it’s reversible.

Democracy scholars, such as William Galston at the Brookings Institution – a centrist think tank, political scientist Yascha Mounk and columnists like Nicholas Kristof tend to focus on the rise of populist and far-right leaders when explaining global democratic decay.

But in democracies, the law, not the president or prime minister, is critical to maintaining the pillars and foundations upon which democracy rests. That is why I consider an Austrian law that curbs access to foreign funding to all Muslim organizations so troubling.

I’m also concerned about a Polish law that consolidates all power over nongovernmental organization funding, whether foreign or domestic, into the hands of a single individual appointed by its prime minister. And I find a Hungarian law, which requires nongovernmental organizations that get more than $28,000 of their funds from other countries to label themselves as funded from abroad on all of their publications, worrisome.

When laws are passed that undermine democracy’s critical foundations, democracy weakens. Laws restricting the independence and strength of nonprofits are one example of this.

The United States

Restrictive laws are even appearing here in the United States, so far only at the state rather than the federal level – aside from a handful of obscure measures. These laws are designed to curb what nonprofits and activists can do.

For example, over the past decade, more than half of all states have introduced so-called “ag-gag laws,” measures designed to silence whistleblowers who reveal animal abuses on industrial farms. However, the U.S. system of checks and balances is slowing and reversing their impact. American courts are finding many of these laws to be in violation of the Constitution.

At the same time, ag-gag laws remain on the books in at least seven states.

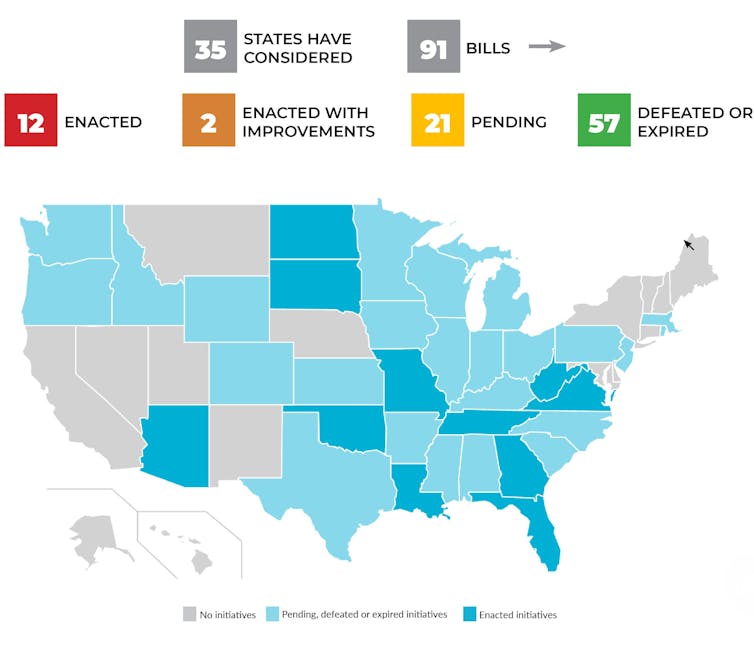

Initiatives at the state and federal level since November 2016 that aim to restrict the rights of Americans to protest are all over the map. International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), CC BY-ND

Similarly, since November 2016, legislators in 35 states have considered more than 91 bills designed to restrict protest activities. For example, a growing number of states, including Missouri, North Dakota, Ohio and Washington have introduced harsh new criminal penalties for protesters who wear hooded jackets or otherwise disguise their identities while protesting. What’s more, states, including Florida, Kentucky, North Carolina and Texas, have proposed laws shielding motorists from liability if they end up injuring or killing protesters who block traffic.

Few of these anti-protest measures, only 11 of 91 considered, have been enacted. Legal challenges could topple many if not all of them. But these measures do, in my view, have the potential to erode American democracy. Chrystie Flournoy Swiney, Doctoral Fellow at Georgetown and Human Rights Attorney, Georgetown University

Chrystie Flournoy Swiney, Doctoral Fellow at Georgetown and Human Rights Attorney, Georgetown University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.