Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, center, signs a bill that creates a new voucher program for thousands of students to attend private schools using taxpayer dollars. Lynne Sladky/AP

By Christopher Lubienski and Joel R Malin | June 7, 2019

For the past couple of decades, proponents of vouchers for private schools have been pushing the idea that vouchers work.

They assert there is a consensus among researchers that voucher programs lead to learning gains for students – in some cases bigger gains than with other reforms and approaches, such as class-size reduction.

They have highlighted studies that show the positive impact of vouchers on various populations. At the very least, they argue, vouchers do no harm.

As researchers who study school choice and education policy, we see a new consensus emerging — including in pro-voucher advocates’ own studies — that vouchers are having mostly no effects or negative effects on student learning. As a result, we see a shift in how voucher proponents are redefining what voucher success represents. They are using a new set of non-academic gains that were not the primary argument to promote vouchers.

How success is defined is particularly important now in light of the fact that Florida and Tennessee – which are both controlled by Republicans – have created new publicly funded voucher programs in May 2019.

In April, a large-scale study — conducted by voucher advocates — found substantial negative impacts for students using vouchers to attend private schools.

Certainly, other studies show a different kind of positive effect on the likelihood of a student enrolling and persisting in college. Other studies also show that vouchers have positive effects on perceptions of school safety, and on avoidance of crime and out-of-wedlock births. But these goals were not what was used to advance vouchers.

Vouchers being pursued politically

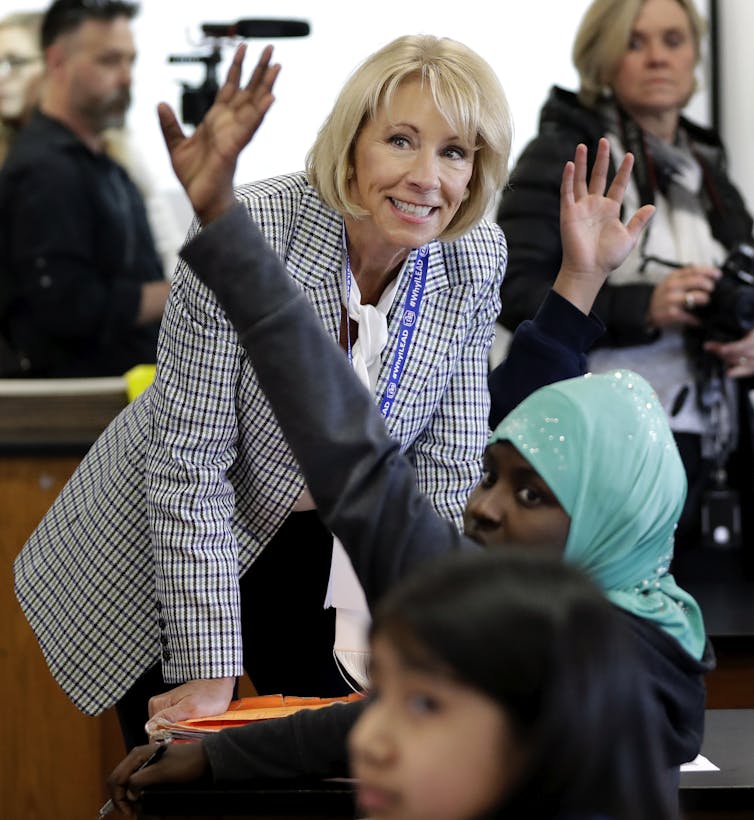

In addition to states, Republicans are pursuing vouchers at the federal level as well. For instance, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos – along with Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas and eight of his fellow Republican senators – are pushing for a voucher-like plan to establish what they refer to as Education Freedom Scholarships. The US$5 billion proposal would enable individual taxpayers and businesses to get dollar-for-dollar tax credits for contributions to “scholarship” organizations. Those organizations would then pass the money to families to use for private schools or other education related expenses for their children.

U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos talks with students in Nashville, Tenn., in April, as lawmakers voted to expand school vouchers. Mark Humphrey/AP

There is a largely partisan divide in Congress concerning the District of Columbia school voucher program – a federally funded school voucher program created under President George W. Bush.

The program, which is authorized under the Scholarships for Opportunities and Results Act, has gotten more than $200 million from Congress and served more than 10,000 children since it began in 2004. It is set to expire in September.

House Democrats are looking for problems with the D.C. voucher program. In response, Republicans are seeking additional information to back up the Trump administration’s proposal to double its funding, from $15 million to $30 million, even though a 2017 evaluation of the program showed “negative impacts on student achievement.”

The voucher advocacy movement

Given all the political interest in vouchers, it pays to revisit how there came to be such as disconnect between what the research shows about the negative impacts of vouchers and their popularity with policymakers.

Starting in the early 1990s, a voucher-advocacy movement emerged to promote the idea that vouchers help students learn. Funded largely by pro-voucher philanthropies such as the Walton Family Foundation, think tanks, such as Cato Institute and The Heritage Foundation, and advocacy organizations, such as EdChoice, made concerted efforts to promote proof of the effectiveness of vouchers. The proof came in the form of a small set of studies of voucher programs for poor children in a select set of cities. The studies were conducted by a group of pro-voucher scholars often funded by those same philanthropies.

For example, a Harvard center funded by pro-voucher organizations, disputed the official state evaluations of voucher programs in Milwaukee and Cleveland to argue that there were small but discernible achievement gains for voucher students.

More recently, teams from the University of Arkansas have been claiming that their studies show that vouchers almost always lead to learning gains for at least some students, do little if any harm to students, and provide all sorts of other benefits. Among other things, they say that vouchers reduce crime and lead parents to become more involved in civic life. The media then pick up these studies.

But the latest research about vouchers calls into question the original, primary claims about their effectiveness.

New evidence emerges

Rigorous research on state-wide programs in Ohio, Indiana and Louisiana, as well as in Washington, D.C., shows large, negative impacts on academic achievement of students using vouchers compared to their peers who stayed in public schools.

Initial hopes by some researchers and voucher advocates that these losses would disappear over time have evaporated as more recent follow-up studies show that the harm is significant and sustained.

Now that there is evidence that vouchers harm student learning, voucher advocates have changed their argument. They say test scores are not that important. Instead, they say policymakers should focus on other measures such as “attainment,” which entails things like the rate at which voucher students enroll in college.

However, some of the most recent research finds that vouchers don’t really lead to better college enrollment, either.

Bad choices

While some advocates downplay the importance of test scores, others, such as DeVos make the argument that vouchers are worthy simply because they give students and families expanded choice.

We believe student learning, the original reason vouchers were promoted, should remain the measure of success. While imperfect, few measures are as readily available to policymakers as test scores in evaluating education reforms. Moreover, advocates should be accountable for the results they said would occur regarding learning gains. But instead, it appears they want to “move the goalposts” they themselves had set up.![]()

Christopher Lubienski, Professor, Indiana University and Joel R Malin, Assistant Professor, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.