By Eric Kyere, The Conversation | July 30, 2020

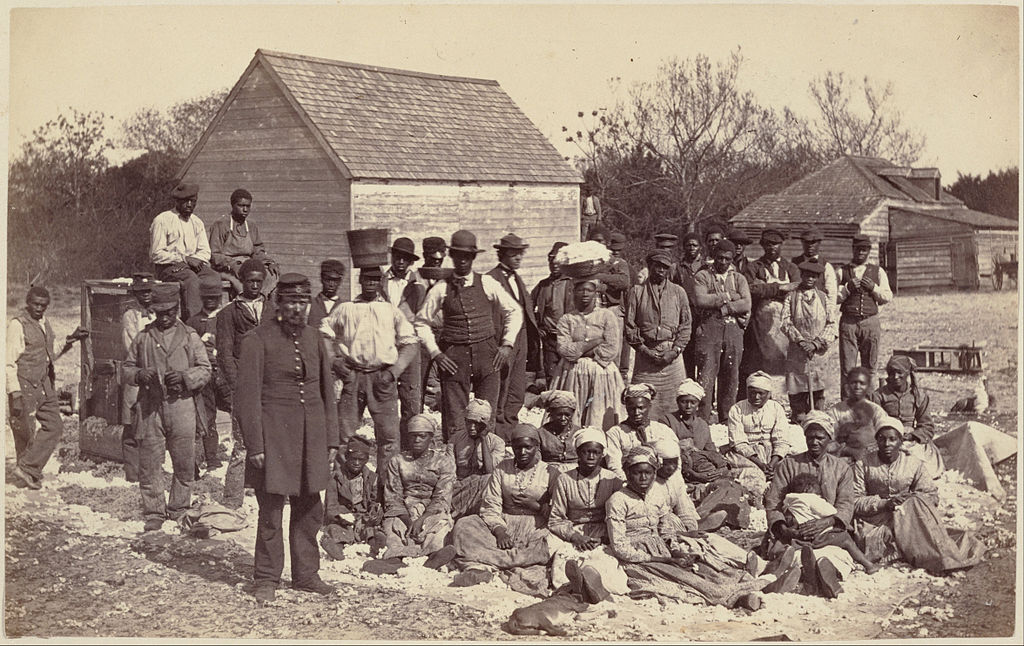

Some critics of Black Lives Matter say the movement itself is racist. Their frequent counterargument: All lives matter. Lost in that view, however, is a historical perspective. Look back to the late 18th century, to the very beginnings of the U.S., and you will see Black lives in this country did not seem to matter at all.

Foremost among the unrelenting cruelties heaped upon enslaved people was the lack of health care for them. Infants and children fared especially poorly. After childbirth, mothers were forced to return to the fields as soon as possible, often having to leave their infants without care or food. The infant mortality rate was estimated at one time to be as high as 50%. Adult people who were enslaved who showed signs of exhaustion or depression were often beaten.

As a professor of social work, I study ways to stop racism, promote social justice, and help the Black community empower itself. A relationship exists between the health of enslaved Blacks and the making of America.

‘Racist medical theory’

White masters, often brutal and violent, dehumanized the enslaved people who worked for them and became wealthy from their work. Slaveholders justified their treatment by relying on the widely accepted view of Black inferiority and the physical differences between Blacks and whites. Racist medical theory, the racist notion that the blacks were inherently inferior and animal-like who needed maltreatment to be sound for work, was a critical element.

Enslaved people were poorly fed, overworked and overcrowded, which promoted germ transmission. So did their housing – bare, cold and windowless, or close to it. Because they were not paid, slaves could not maintain personal hygiene. Clothes went unwashed, baths were infrequent, dental care was limited, and beds remained unclean. Body lice, ringworm and bedbugs were common.

This treatment began in slave dungeons, built by Europeans on the coastal shores of Africa, where enslaved Blacks awaited shipment to the New World. In Ghana, for example, perhaps 200 were cloistered in tiny spaces where they ate, slept, urinated and defecated. Archaeological research has shown the dirt floors were soaked in vomit, urine, feces and menstrual blood. Conditions within the dungeon were so deadly that cleaning them was discouraged; those who tried risked smallpox and intestinal infections.

A dungeon for enslaved females at the Cape Coast Fort in Ghana. Eric Kyere, CC BY-SA

Sick slaves rarely saw doctors

Diseases among the enslaved people in the colonies and later the states were common and at a disparate rate when compared to whites: typhus, measles, mumps, chicken pox, typhoid and more. Only as a last resort did the slave owner bring in a doctor.

Instead, the white master and his wife would provide the health care, though rarely were either one trained physicians. Older enslaved women also helped, and brought their knowledge of herbs, roots, plants and midwifery from Africa to the Americas.

As with everything else, Blacks had no say about their care. And if a doctor was involved, Black patients were not necessarily told anything about their condition. The medical report went directly to the slave owner.

Black women played multiple roles. Of course, they were part of the labor force. And they took care of the sick. But they were also the machinery for producing more black bodies. After the mid-Atlantic slave trade was banned, slave owners needed a new source of labor. A pregnant enslaved woman provided that possibility. The birth of a baby born into slavery meant profits that potentially lasted generations, a product requiring little investment.

Some of the Black women were used in medical experiments; much of the research, some conducted without anesthesia, focused on maternal health. As the white scientists inflicted tremendous pain on the pregnant women, the infants being carried sometimes died. Through the torture of these enslaved women, many white physicians and white medical institutions gained considerable fame and wealth.

Adverse health consequences for Blacks facilitated the establishment of some medical advances, such as the invention of the speculum for gynecological exams. One enslaved woman reportedly endured 30 gynecological surgeries without anesthesia. Medical interests and also economic and political interests were served.

More than 150 years later, the health disparities of Black and white Americans remain. To fix what is wrong today, an understanding of the inequities of the past is an imperative. Only then can we begin to dismantle the structural racism that is replete within the American system. Knowledge of the history is necessary to explore and identify the underlying mechanisms to understand how racism revives itself to continue to produce health disparities, and ways to interrupt it.![]()

Eric Kyere, Assistant professor, social work, IUPUI

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.