By William H. Calvin, The Conversation | August 18, 2020

Heat waves are the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, not the more photogenic windstorms and floods. Hotter summers from climate change are causing concerns over new dangers to people.

As a medical school professor, I’ve focused on physiology, neuroscience, the evolution of the big brain and, more recently, climate science and civilization’s vulnerability to abrupt shocks from climate change. Today I’m wearing my physiologist’s hat and asking: How do heat waves kill?

We can take the heat – usually

Thanks to our meat-eating ancestors, who could run down prey in long midday chases on the African savanna, we humans are able to keep our body temperature in the range where we function best in a wide range of conditions, even those combining extreme heat with extreme exertion.

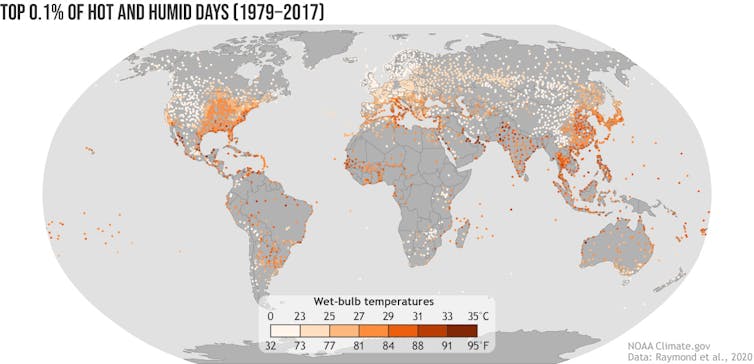

So, what’s the problem? Humidity. There wasn’t very much of it in the African Rift Valley 2 million years ago to shape us. And evolution does not think ahead.

Unlike the African savanna, the eastern half of the U.S. can be both hot and humid in the summer, thanks to water vapor from the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. I grew up in Kansas City in the midst of Gulf Stream humidity wafted north by the monsoon circulation, then studied physics at Northwestern University on the shores of Lake Michigan. I experienced high-humidity heat waves there, but none so severe as the Chicago high-humidity heat wave in 1995 that killed 739 people in a week.

Normally sweat evaporates off your skin and you cool down. But with high humidity, the air is already saturated with water vapor, and so evaporative cooling stops. However, you keep sweating anyway, threatening dehydration.

To spot heatstroke, check for confusion

What can overwhelm a person is a heat source that you can neither escape nor counter. Overheated people suffer from painful involuntary muscle spasms and heat exhaustion. One of the criteria for when these are advancing to the potentially fatal heatstroke is when someone is no longer thinking normally. They look flushed and their conversation becomes incoherent.

Stay hydrated to avoid dangerous overheating. Avoid drinks with caffeine or alcohol, especially before strenuous work or exercise. U.S. Air Force photo by Airman Rhett Isbell

What should you do if you think someone is overheated? Test for confusion about time or place. Ask “Where are you? When did you come here? Who did you come with?” If you get incoherent answers, treat it as an emergency.

Take charge. After directing someone to phone for help, arrange bystanders so they cast shade over the victim. Shielding the person’s billfold and phone, then pour bottled water to soak the clothing and hair. If the victim can sit up and drink, provide water but don’t insist.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]Heat waves can kill via the dehydration caused by heavy sweating; the altered sodium and potassium concentrations in the blood confuse both heart and nerve cells, and so breathing or heartbeat may suddenly stop.

The other major route to a fatal outcome is that prolonged overheating can create widespread inflammation, not just a flushed face. The dilation of so many small blood vessels means that much venous blood pools, failing to return to the heart. Recovery can take two to 12 months.

An unbroken series of nights, when it is too hot to sleep, poses a major threat. Should a sleepy caregiver become confused or exhausted, and no longer provide water and wet towels for children or seniors every hour, they may die.

Mega heat waves and other extreme weather surges

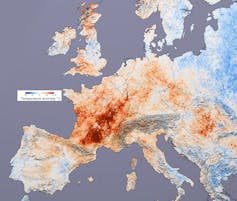

The first mega heat wave which, in a few weeks, killed around 70,000 people, about a hundred times as many as did a typical big heat wave in the 20th century. Reto Stockli and Robert Simmon, based upon data provided by the MODIS Land Science Team, CC BY

Stalled jet stream loops in the atmosphere have led to two “mega heat waves.” One in Europe killed 70,000 people in 2003, leading to the term “mega.” Some thought that it was one of those once-in-a-million events, unlikely to be seen again in our lifetime.

Then, a mere seven years later, 56,000 were killed in Russia. This second mega also ruined the Russian wheat crop; they immediately stopped exporting, setting the stage for the Arab Spring food riots and uprisings of 2011.

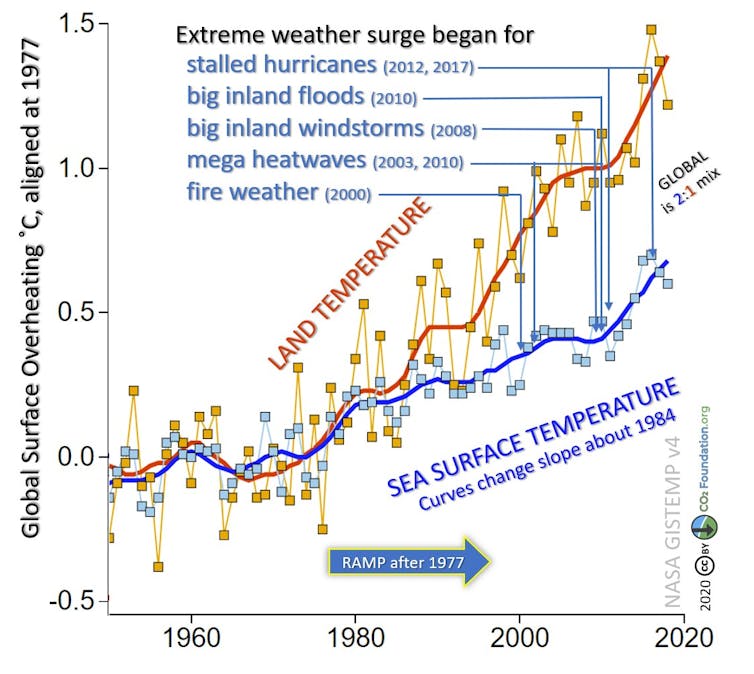

A heating ramp began in 1977 for both land and ocean surface. After 1984, land temperatures rose 150% faster than ocean surface. The problem with big heat waves, however, is with their longer duration, not the extra degree or two. Beginning about 2000, a series of five sustained surges in extreme weather occurred. All involve an increased duration of events, usually secondary to a stalled jet stream loop, unable to drift eastward, and so clouds fail to arrive to cool things off. Extreme Weather and What to Do About It, by William Calvin; data from NASA/GIS

In the 1960s, extreme weather events were predicted to become more common with overheating. It wasn’t gradual: In the last 20 years, extreme weather events have surged. Besides the mega heat waves, the number of billion-dollar severe storms is up seven times in the U.S., the number of severe inland floods is up four times, and the number of billion-dollar wildfires is now five times the 20th-century numbers. Hurricane Harvey battered Houston for five days with high winds and received a year’s worth of rain atop the storm surge.

As I describe in “Extreme Weather and What to Do About It,” this sort of abrupt climate shift is what we are now up against, not just the slow rise in average global temperature.

Organizing for a heat wave

When an unbroken series of hot nights are forecast, opening cooling centers is not enough. Neighbors should organize in advance, so that the able regularly check up on the less able, testing for heatstroke with questions that might reveal confusion. Phone before visiting so that you can ask, “When was the last time the phone rang?” Leave behind cool six-packs of bottled water and snacks for bedside consumption.

In the meantime, remind your elected officials that they must prepare for more big heat waves. They also need to address the cause with big projects that quickly remove excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to cool us off. We must now back out of the danger zone for even worse extreme weather. As we have already seen, it can take big steps as it worsens, even though overheating itself merely creeps up.

William H. Calvin, Professor Emeritus, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.