In the 19th century, white families in the U.S. could easily acquire real estate. This was never the case for Black Americans. U.S. National Archives, CC BY-NC

By J.M. Opal | December 19, 2018

When Americans study their 19th-century history, they tend to look at its great conflicts, especially the epic clash over slavery. They are less likely to recall its broad areas of agreement.

But what if those agreements are still shaping the present? What if Americans are still coping with their effects? The steep inequalities between white and Black wealth in America, for example, has a lot to do with a 19th-century consensus over public lands.

Land grants from British officials to colonial families date back to the 1600s in North America, but the general idea took on new life with the 1801 presidential election of Thomas Jefferson, a Virginia slave-owner and radical who saw all white men as equally superior to everyone else. To provide them with farms, he purchased Louisiana from Napoleon.

Rights of soil

Jefferson’s Democratic party organized the sale of public land in small units on easy credit. When settlers fell behind on payments, Congress gave them more time in repeated Relief Acts during the 1810s and 1820s.

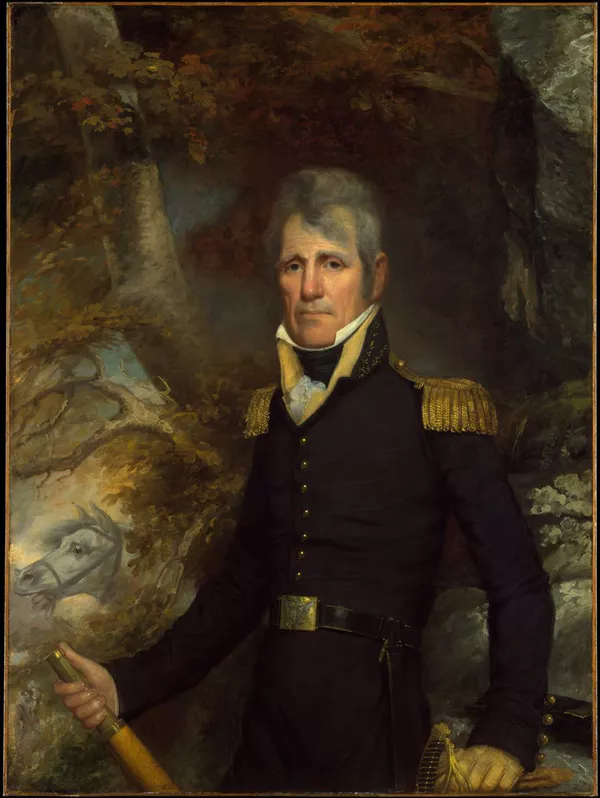

President Andrew Jackson followed in the 1830s by expelling some 70,000 Choctaws, Creeks, Cherokees, Chickasaws and Seminoles from their farms and villages. White families poured into the stolen ground with their slaves, creating a Cotton Kingdom that quickly spread from Florida to Texas.

By the time the Senate debated the General Pre-Emption Act of 1841, which gave settlers first claim to buy frontier plots at regulated prices, the United States had tens of millions of acres at its disposal. With so much room for everyone but the Indigenous inhabitants, pre-emption had wide support.

The senators did argue over the pre-emption rights of immigrants from Britain or Germany. By a vote of 30-12, however, they decided that European-born settlers had the same claim to the continent as native-born citizens. As Democratic Sen. Thomas Benton put it, all men were equal when it came to “the rights of property.”

During this same discussion, a member of the rival Whig Party moved to put the word “white” into the bill so that no Black settlers could make pre-emptions.

This passed 37-1.

In sum, a bipartisan goal of early U.S. foreign and domestic policy was to insure that white families could easily acquire real estate — then, as now, the major asset for most households. This was never the case for Black Americans, who were seen as a separate and hostile “nation” within the country.

Landless in America

Hunted in the South and despised in the North, Black Americans could only buy western land from speculators, who easily cheated people with little access to courts and no standing at the polls. And so most scraped by as labourers rather than landowners.

The pattern continued after the Civil War, when plans to give former slaves some of the lands on which they had toiled went nowhere even as Congress made western homesteads free for everyone else.

By the end of the century, railroads and other corporations had become the big recipients of federal largesse. Nonetheless, millions of ordinary white families began the modern age on their little patches of America.

Their real estate offered both an early form of social security and a base of family capital, an economic foundation from which to enter a more urban and industrial society. It also made them feel like the only “real” Americans, the ones who literally owned the place.

By contrast, Black families faced a vicious cycle of landless marginality: as agricultural or domestic workers, they were excluded from the first Social Security Act of 1935, making it even harder for them to protect family fortunes. As second-class citizens and servicemen, they rarely benefited from the so-called GI Bill of Rights of 1944, which made home ownership much easier for nearly eight million veterans.

No wonder that even low-income whites were far more likely to own homes or businesses than Black families when the Great Recession struck 10 years ago. Since then, wealth disparities have grown again: the Federal Reserve of the United States now estimates that the average white household has 10 times the total assets of its Black counterpart.

History and mythology

These grim facts do not stop the “blood and soil” nationalists of Donald Trump’s America from feeling victimized. Nothing ever will.

The bigger problem is that a much wider part of the U.S. population subscribes to frontier mythologies, in which hardy white folk built the country without anyone’s help or permission. And why shouldn’t they believe so, if we don’t offer more honest accounts of the frontier?

For all its faults, history is better than mythology. In this case, it can illuminate how European blood gave exclusive access to American soil, enriching debates about today’s inequalities.

Perhaps it can even help Americans build a truly multi-racial nation, a society in which everyone feels equally American.![]()

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.