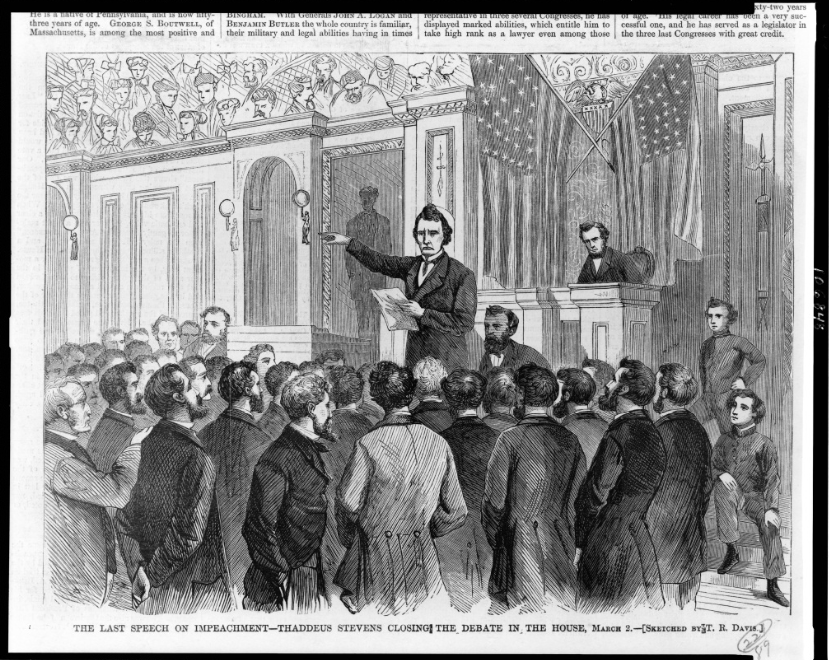

Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, a Radical Republican, gave the last speech during House debate on articles of impeachment against President Andrew Johnson on March 2, 1868. Johnson became the first president impeached by the House, but he was later acquitted by the Senate by one vote. Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

“The President, Vice President and all Civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

— U.S. Constitution, Article II, section 4

The U.S. Constitution gives the House of Representatives the sole power to impeach an official, and it makes the Senate the sole court for impeachment trials. The power of impeachment is limited to removal from office but also provides for a removed officer to be disqualified from holding future office. Fines and potential jail time for crimes committed while in office are left to civil courts.

Origins

Impeachment comes from British constitutional history. The process evolved from the 14th century as a way for parliament to hold the king’s ministers accountable for their public actions. Impeachment, as Alexander Hamilton of New York explained in Federalist 65, varies from civil or criminal courts in that it strictly involves the “misconduct of public men, or in other words from the abuse or violation of some public trust.” Individual state constitutions had provided for impeachment for “maladministration” or “corruption” before the U.S. Constitution was written. And the founders, fearing the potential for abuse of executive power, considered impeachment so important that they made it part of the Constitution even before they defined the contours of the presidency.

Constitutional Framing

During the Federal Constitutional Convention, the framers addressed whether even to include impeachment trials in the Constitution, the venue and process for such trials, what crimes should warrant impeachment, and the likelihood of conviction. Rufus King of Massachusetts argued that having the legislative branch pass judgment on the executive would undermine the separation of powers; better to let elections punish a President. “The Executive was to hold his place for a limited term like the members of the Legislature,” King said, so “he would periodically be tried for his behaviour by his electors.” Massachusetts’s Elbridge Gerry, however, said impeachment was a way to keep the executive in check: “A good magistrate will not fear [impeachments]. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them.”

Another issue arose regarding whether Congress might lack the resolve to try and convict a sitting President. Presidents, some delegates observed, controlled executive appointments which ambitious Members of Congress might find desirable. Delegates to the Convention also remained undecided on the venue for impeachment trials. The Virginia Plan, which set the agenda for the Convention, initially contemplated using the judicial branch. Again, though, the founders chose to follow the British example, where the House of Commons brought charges against officers and the House of Lords considered them at trial. Ultimately, the founders decided that during presidential impeachment trials, the House would manage the prosecution, while the Chief Justice would preside over the Senate during the trial.

The founders also addressed what crimes constituted grounds for impeachment. Treason and bribery were obvious choices, but George Mason of Virginia thought those crimes did not include a large number of punishable offenses against the state. James Madison of Virginia objected to using the term “maladministration” because it was too vague. Mason then substituted “other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” in addition to treason and bribery. The term “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” was a technical term—again borrowed from British legal practice—that denoted crimes by public officials against the government. Mason’s revision was accepted without further debate. But subsequent experience demonstrated the revised phrase failed to clarify what constituted impeachable offenses.

The House’s Role

The House brings impeachment charges against federal officials as part of its oversight and investigatory responsibilities. Individual Members of the House can introduce impeachment resolutions like ordinary bills, or the House could initiate proceedings by passing a resolution authorizing an inquiry. The Committee on the Judiciary ordinarily has jurisdiction over impeachments, but special committees investigated charges before the Judiciary Committee was created in 1813. The committee then chooses whether to pursue articles of impeachment against the accused official and report them to the full House. If the articles are adopted (by simple majority vote), the House appoints Members by resolution to manage the ensuing Senate trial on its behalf. These managers act as prosecutors in the Senate and are usually members of the Judiciary Committee. The number of managers has varied across impeachment trials but has traditionally been an odd number. The partisan composition of managers has also varied depending on the nature of the impeachment, but the managers, by definition, always support the House’s impeachment action.

The Use of Impeachment

The House has initiated impeachment proceedings more than 60 times but less than a third have led to full impeachments. Just eight—all federal judges—have been convicted and removed from office by the Senate. Outside of the 15 federal judges impeached by the House, two Presidents (Andrew Johnson in 1868 and William Jefferson (Bill) Clinton in 1998), a cabinet secretary (William Belknap in 1876), and a U.S. Senator (William Blount of Tennessee in 1797) have also been impeached.

Blount’s impeachment trial—the first ever conducted—established the principle that Members of Congress and Senators were not “Civil Officers” under the Constitution, and accordingly, they could only be removed from office by a two-thirds vote for expulsion by their respective chambers. Blount, who had been accused of instigating an insurrection of American Indians to further British interests in Florida, was not convicted, but the Senate did expel him. Other impeachments have featured judges taking the bench when drunk or profiting from their position. The trial of President Johnson, however, focused on whether the President could remove cabinet officers without obtaining Congress’s approval. Johnson’s acquittal firmly set the precedent—debated from the beginning of the nation—that the President may remove appointees even if they required Senate confirmation to hold office.