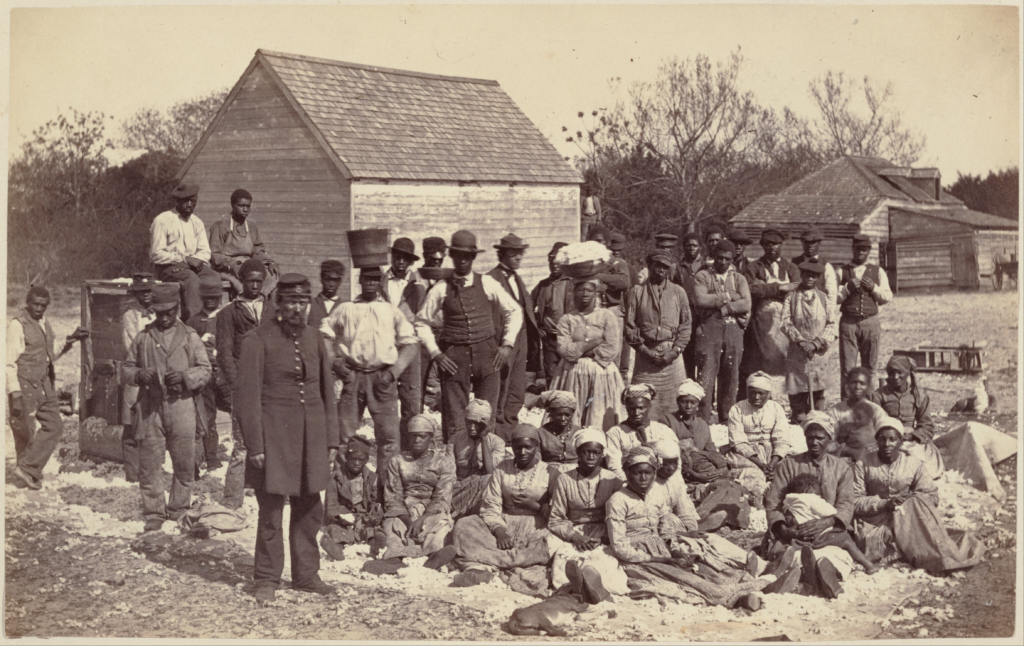

Slaves of General Thomas F. Drayton 1862. Several 2020 presidential candidates have called for reparations for slavery in the U.S. Getty Center [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Does the United States owe descendants of slaves reparations?

It’s a question being asked more frequently of Democrats running for the 2020 presidential nomination. Many have expressed varying degrees of support for reparations, giving the idea the greatest prominence it’s ever had among leading politicians.

Although the notion of compensating freed slaves has been around since at least the Civil War, providing reparations for their descendants has never really gained much traction in the United States, as I learned while researching my book “Making Whole What Has Been Smashed.”

Is anything different now?

Reparations are rare

Historically, the term “reparations” dealt primarily with the indemnification of states ravaged by war, such as those required of the Germans by the Versailles Treaty after World War I.

In the aftermath of World War II, however, the term began to acquire a broader meaning, extending to compensation for those injured by the actions of a state.

Still, such compensation has happened only rarely.

Germany paid Holocaust survivors US$927 million – or $8.84 billion today – in compensation as part of the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement, most of it going to the newly created state of Israel to defray the costs of resettlement.

Later, the U.S. offered “redress” to some 82,000 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated as “enemy aliens” during World War II. The 1988 Civil Liberties Act granted a presidential apology and $20,000 to each living person who had been detained based on the recommendations of a commission created by Congress in 1980 to examine the causes of the “internment.”

But this payback was intended to be very limited. During the debate, then-Sen. Ernest Hollings worried, “Where do we draw the line against reparations to the countless other groups of Americans who have suffered because of actions of the U.S. government?”

And the law explicitly says compensation would only be provided to victims still alive in order to preclude reparations claims by the descendants of black slaves and others.

‘40 acres and a mule’

Efforts to avoid establishing a precedent for reparations arose in part because former slaves and their descendants have long sought some sort of compensation for their suffering under slavery and segregation. These efforts have achieved little.

W. E. B. Du Bois called for reparations. Addison N. Scurlock, CC BY

Perhaps the best-known measure intended to get blacks on their feet after the Civil War was General William Sherman’s promise of land and loaned mules to work it.

Yet after taking office in 1865, President Andrew Johnson rescinded efforts to distribute land to those who were freed. Scholar-activist W. E. B. Du Bois thus observed that “the vision of ‘forty acres and a mule’ … was destined in most cases to bitter disappointment.”

‘Freedom is not enough’

A century after the Civil War, however, President Lyndon Johnson hinted at the need for reparations when he pushed through civil rights legislation intended to make blacks full citizens.

During a speech at Howard University in 1965, he declared: “Freedom is not enough. … It is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity.”

Although Johnson didn’t call explicitly for reparations, he urged something more than just equal rights for blacks – something that would rectify the economic disadvantage blacks faced. The speech has often been seen as a harbinger of affirmative action.

Two years later, in the aftermath of urban riots in Newark, Detroit and elsewhere, Johnson created the Kerner Commission to investigate the causes and recommend remedies. The commission found that “white racism” was the basic cause of the racial unrest and proposed massive investment in black communities.

Although the report was a best-seller, Johnson found the conclusions politically distasteful and distanced himself from the commission.

Martin Luther King Jr. agreed with these critical assessments of black deprivation, but generally couched his appeals for addressing poverty in interracial terms. King did once indicate that he was coming to Washington “for a check,” but this was a rare aside.

The heart of King’s “Poor People’s Campaign,” his main focus toward the end of his life, was a universal basic income, not reparations.

But others would pick up the reparations baton. Black radical James Forman, for example, stormed Manhattan’s famously progressive Riverside Church in May 1969 to demand $500 million from “the white Christian churches and Jewish synagogues that are part and parcel of the capitalist system.” This and other demands formed the basis of the Black National Economic Conference’s “Black Manifesto.”

Calls for a commission

Little came of these efforts until decades later when then-Congressman John Conyers introduced the first bill on the issue in 1989.

It proposed a commission to “study and consider a national apology and proposal for reparations for the institution of slavery, its subsequent de jure and de facto racial and economic discrimination against African Americans, and the impact of these forces on living African Americans, [and] to make recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies.”

The Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act has been proposed in every legislature since and never garnered much support. Even during President Barack Obama’s tenure in the Oval Office, little changed, despite the appearance of author Ta-Nehisi Coates’ much-discussed 2014 plea for reparations.

Indeed, shortly before he left office, Obama told Coates that, as a political matter, reparations for black people was far less likely than a “progressive program for lifting up all people.”

Different this time?

Heading into 2020, some believe that the time for reparations may have come.

A driving force behind the persistence of reparations is just how stark the racial differences remain. Relative to whites, blacks tend to have lower educational attainment, rates of home ownership and life expectancy but higher rates of poverty, incarceration, unemployment and life-threatening diseases. The wealth gap between whites and blacks is very large, and wage inequality is likely making it worse.

But are all these disparities rooted in slavery and segregation? This is where a congressional inquiry, which may finally be politically palatable thanks to the growing embrace of the idea among prominent Democrats, would come in.

Success, which will require legislation, will depend on building bipartisan support for the inquiry. Accordingly, I believe it’s best to avoid talk of “reparations.” After all, most Americans oppose them and always have.

First, get the commission and let it determine the causes of racial inequalities and the form that remedies should take. As poverty is not an affliction of blacks alone, the U.S. must also address the poverty that affects many others as well.

If the commission is given the opportunity to explore the causes of and remedies for racial inequality, however, perhaps Americans can finally move toward rectifying the inequities that beset blacks as a result of their country’s history of slavery, segregation and discrimination.

John Torpey, Presidential Professor of Sociology and History, Graduate Center, City University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.