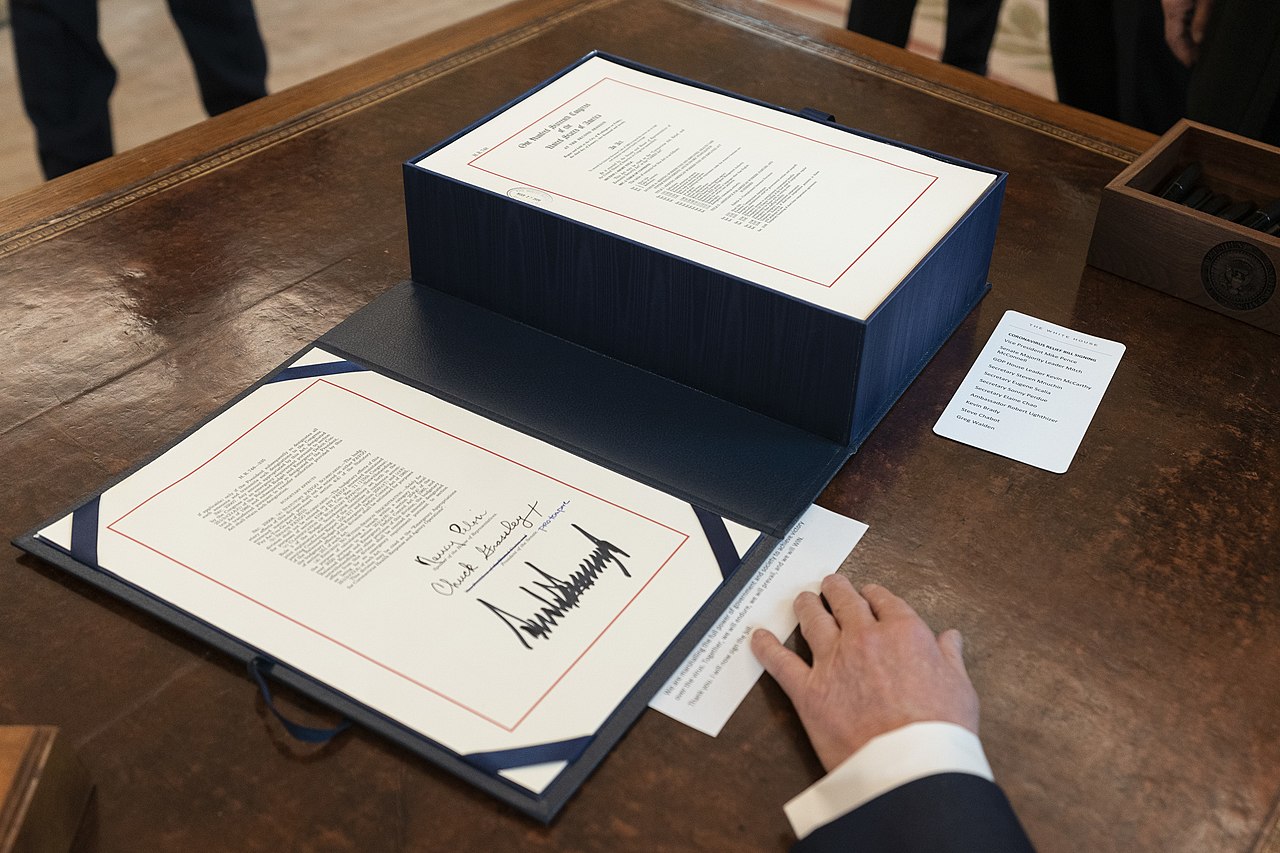

President Donald J. Trump’s signature is seen on H.R. 748, the CARES Act, the $2.2 trillion assistance package to help American workers, small businesses and industries crippled by the economic disruption caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

By Allan Sloan, Propublica | June 8, 2020

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Do you want to see how legislation that was supposed to be a bailout for our economy ended up committing almost as much taxpayer money to help a relative handful of the non-needy as it spent to help tens of millions of people in need? Then let’s step back and revisit parts of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act and look at some of the numbers involved.

The best-known feature of the CARES Act, as it’s known, is the cash grant of up to $1,200 per adult and $500 per child for households whose income was less than $99,000 for single taxpayers and $198,000 for couples. These grants are nontaxable, which makes them even more valuable. Some 159 million stimulus payments have gone out, according to the IRS.

The income limits suggested that the plan benefits the people most in need, those most likely to spend their stimulus payments and thus help the economy. The rhetoric conveyed the same: “The CARES Act Provides Assistance to Workers And Their Families” is how the Treasury’s website puts it. There were no grants to more-fortunate people, who for the most part aren’t in financial distress and are less likely than the less-fortunate to spend any money that Uncle Sam sent them.

But when I began looking at details of the legislation, I realized that several of its provisions quietly provided benefits that were worth much more than $1,200 to some upper-middle-class people who didn’t qualify for stimulus payments. Some other provisions provided vastly bigger benefits to the rich, to corporations and to a relative handful of ultra-rich folks.

So let me show you five provisions of the legislation that benefited the upper middle class (including yours truly); the families of Donald Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner; high-income people who make large charitable donations; and Boeing and other corporations that are showing losses; as well as indirectly benefited people who have substantial investments in U.S. stocks.

These five provisions that help the well-heeled will cost the Treasury — which is to say, U.S. taxpayers — an estimated $257.95 billion for the 2020 calendar year. That’s nearly as much as the estimated $292.37 billion price tag for the stimulus grants to regular folks. The numbers are from Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, the official scorekeeper of the financial impact that legislation has on the Treasury. (I used those figures to calculate the spending for the 2020 calendar year rather than for 10 federal fiscal years because I’m interested in today’s impact, not the projected long-term impact.)

I’m writing this now, more than two months after the CARES Act took effect, as a cautionary tale. That’s because with massive unemployment upon us and the fall elections drawing near, there’s a temptation for Congress and Trump to produce legislation that will help needy people a bit but help the non-needy a lot more by doing things like reducing capital gains taxes.

Now, let me take you through the provisions, only one of which — the break for the Trumps, the Kushners and their ilk — has attracted meaningful public attention.

Eliminating Required Distributions From Retirement Accounts: $11.72 billion

People ages 72 and up who have IRAs or 401(k)s or other “defined contribution” retirement accounts must take federally taxable required minimum distributions from them every year. (Some states also tax these distributions.) People who inherit such accounts are also required to take annual distributions, regardless of their age.

The required distribution amount is based on year-end age and account balances. For example, if you were 75 at year-end — as I was — your RMD for this year is 4.37% of your year-end 2019 retirement account balances. If you were 76, it’s 4.55%.

But this year, thanks to the CARES Act, I don’t have to take any retirement distributions at all.

Not having to take distributions matters a lot to some people. For instance, if I took my full RMD this year, which I don’t plan to do, it would be one of my larger income sources. And I would have to pay federal and state income tax on it, regardless of whether I spent the money or saved it.

I’d like to tell you how many people the JCT expects to benefit from this year’s RMD waiver; how much their distributions would have totaled and what the tax rate on them would have been; and how many people the JCT expects to take distributions this year even though they’re not required to take them. Alas, the JCT doesn’t disclose this information and declined to share it with me.

But even though I don’t have specific numbers, it’s clear that most of the benefit from this year’s RMD waiver goes to well-off people. Why? Because people who need retirement account money to live on are going to take distributions, and people who don’t need the money are unlikely to take distributions.

The reason for the no-RMD provision is that the stock market was sinking rapidly in March, when the CARES Act was being discussed. The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, for example, fell by 30.8% from the end of 2019 through its low for 2020 (at least so far) on March 23, a few days before Trump signed the CARES Act legislation. Congress didn’t want to penalize retirees by forcing them to sell stock during a market crash.

So if someone with a 4.37% required distribution had money in an S&P 500 index fund, our investor would have had to withdraw 6.32% of the fund’s balance (4.37 divided by 69.2) rather than 4.37% of it if the investor took the distribution on March 23. That would have hurt our investor’s future financial security.

If the market fell by 50% through year-end, which in the scary days of March seemed to be a distinct possibility and could still happen, our theoretical investor would have to cash out 8.74% of the account if RMDs were still required.

There were other ways to deal with this problem, such as letting people take a pass on their first $15,000 of RMDs, rather than giving a big break to the likes of me and a far bigger break to people with far larger retirement accounts than mine. But Congress and Trump didn’t do that.

Charitable Deductions: $4.83 billion

Normally, people who itemize deductions on their federal tax return can deduct no more than 60% of their adjusted gross income for charitable contributions. But for this year, the limit is 100% of AGI.

The Tax Policy Center, whose research helped inform this article, estimates that about two-thirds of the people who donated more than 60% of their AGI in past years had incomes of less than $100,000. But although such people accounted for the bulk of those making such large contributions relative to their income, the TPC says, “Most of the value of the deduction goes to just a small number of the very wealthy.”

The theory behind raising the limit this year is that it will encourage people to make larger donations than they otherwise would. But I can’t imagine how this provision — like the provision allowing people who take the standard deduction to subtract $300 from their taxable income for charitable contributions — is going to significantly increase donations to charities trying to help people cope with COVID-19.

The $4.83 billion JCT number for this provision’s cost to the Treasury includes tax savings for both individuals and corporations.

Pass-Through Entities: $140.61 billion

Now, we come to the huge item that benefits the likes of Trump and Kushner, their families, other wealthy real estate types, hedge fund investors and all sorts of ultra-high-income people, who derive large amounts of money from partnerships, LLCs and other so-called pass-through entities.

As you’ll see in a bit, this big-time break provides a big-time benefit to a relative handful of people.

Now that it’s a fait accompli, this provision is belatedly getting a lot of media attention. So I’ll spare you most of the details about how it allows the ultra-wealthy to use paper losses to offset income that was taxed in previous years, when tax rates were higher than they are now, and get refunds based on those old, higher rates.

Suffice it to say that the JCT estimates that about 82% of these benefits — let’s call it $115 billion — will go to about 43,000 taxpayers with $1 million or more in annual income. That’s an average of about $2.68 million each.

The new proposed stimulus package passed by the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives — the HEROES (for Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions) Act — would repeal this provision. However, its prospects for passage in the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has called the HEROES Act a “totally unserious effort,” seem remote. He and other Senate Republicans insisted on making the break for pass-through entities part of the CARES legislation. It’s hard to imagine them allowing any new bailout legislation to reverse that benefit. I’m sure Democrats realized this but wanted to go on record as opposing the pass-through break.

The HEROES Act would also repeal the $10,000 limit on deductions for state and local income and real estate taxes, which Republicans included in the 2017 tax cut legislation to reduce the cost to the Treasury of the big cuts they gave to corporations and ultra-high-income people. (Not coincidentally, the cap hurt people in high-income, high-tax blue states.) It’s hard to imagine this provision becoming law, either.

Now, let’s look at two corporate tax breaks inserted in the CARES Act. One lets corporations increase their interest deductions; the second lets them use tax losses from 2018, 2019 and this year to get immediate, substantial refunds rather than having to wait until they show future profits that offset those losses.

The people who benefit most from these corporate tax breaks, of course, are the corporations’ owners. (Workers, in theory, benefit to some extent, as well.)

By increasing companies’ cash flows and reported earnings, these breaks help the share prices of corporations whose stock is publicly traded and help increase the value of privately held corporations.

Stock ownership by individuals is concentrated among higher-income people.

Corporate Interest Deductions: $12.09 billion

One of the reforms of the 2017 tax act was reducing the amount of interest that corporations could deduct on their federal tax returns. The idea was to reduce the attractiveness of debt, which is subsidized by taxpayers and carries big risks to corporate owners as well as employees. (For examples, see the recent bankruptcies of Neiman Marcus and J. Crew, which were burdened with debt, part of it incurred to pay fees and distributions to the buyout firms that had taken them over.)

The CARES Act undid part of the 2017 act by increasing the deductible level to 50% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization from the previous 30%.

Like some of the other provisions that we’ve looked at, this doesn’t involve a lot of money relative to the numbers that we’re dealing with. But it’s symbolic. And the people benefiting the most from it because they have major investments in stocks aren’t likely to be worrying about how to pay for food or avoid losing their homes.

Corporate Loss Treatment: $88.70 billion

This does the same kind of thing for corporations that the pass-through provision we discussed earlier does for LLCs and partnerships and such. But it hasn’t attracted anything like the same attention that the pass-through giveaway has gotten because it doesn’t involve names like Trump and Kushner.

Until now, corporations that had losses last year and this year could carry them forward to offset taxes for future years, but they couldn’t apply them to get refunds of taxes paid in previous years.

Corporations can now apply losses from this year, last year and 2018 to income from the previous five years. That’s going to be a big deal for companies — can you say Boeing? — that are likely to show losses.

What’s more, these companies can get refunds of up to 35% of the losses they carry back to 2017 and earlier years, even though the corporate tax rate is now only 21%. The rationale is that because the corporate tax rate was 35% before 2018, companies should be able to get refunds today based on what they paid then, not on what they’d be paying now.

So this pays off on multiple levels: The beneficiaries not only benefit today from current and recent losses rather than having to wait until they have profits in the future, but they get a much bigger bang for the buck.

Our country is suffering through major, major problems. We’ve got more than 100,000 people dead from COVID-19, unemployment levels not seen since the Great Depression, and protests and civil unrest in cities and towns across the country. We’re appropriately adding trillions of dollars to our national debt to try to forestall an economic meltdown. Let’s just hope that further federal aid goes to those who really need it. And doesn’t go to those who don’t.