By Lawrence Lanahan | May 4, 2019

This story is a part of our Map to the Middle Class project, in which readers ask questions about educational pathways to financial stability and then we investigate. This question comes from Susanna Williams: Jobs don’t require college degrees. Employers do. Why do employers ask for college degrees as a qualification? To submit your question or vote on our next topic, click here.

BOSTON — Ryan Tillman-French sat at his seventh-floor desk early on a Thursday morning, the skyscrapers of downtown Boston crowding the windows behind him.

On a laptop in the nearly empty office, he worked on code for a webpage he was developing for his employer, the learning materials company Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. In half an hour, he needed to join a conference call about changes to the company’s website.

He had been at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for four months. Coding he liked. Meetings, not so much.

“That’s one thing I wasn’t warned about when it comes to the corporate world,” he said. “So many meetings.”

Tillman-French, 26, grew up in a Detroit neighborhood where few people around him had jobs. He received an associate degree, hoping to eventually get a bachelor’s and work as a financial adviser. Instead, he bounced from one unfulfilling job to the next in the hospitality and restaurant industries. In the fall of 2017, he moved to Boston and enrolled in a community college, planning to transfer to a four-year program.

One day, a friend forwarded an email about Resilient Coders, a boot camp that trains people of color for web development and software engineering jobs. On a lark, Tillman-French went to a Resilient Coders hackathon, and the passionate staff there sold him on the opportunity. After he finished the 14-week program, he said, he had over two dozen interviews. Three employers asked him back. Only Houghton Mifflin Harcourt made an offer.

Several years ago, Tillman-French’s résumé would likely have ended up in the trash. Until last summer, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt screened out web developer applicants who lacked a four-year degree.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt wasn’t alone in that practice. The previous decade saw a spike in the number of job listings requiring a bachelor’s degree, even for so-called middle-skills jobs — think executive secretaries, production supervisors, IT help-desk workers — that have traditionally been filled by workers with an associate degree or less. Analysts say that this “degree inflation,” as they call it, has shrunk opportunities for upward mobility for Americans without four-year degrees.

But now some workforce organizations, researchers and regional civic leaders are pushing back — persuading companies to look beyond academic credentials and to instead hire people based on their skills. A growing number of businesses are listening. In the past few years, Apple, Google, IBM and other high-profile companies have stripped the bachelor’s degree requirement from many of their positions.

If this movement continues to gather steam, researchers say, it could aid not only individual job seekers but also the U.S. economy by helping businesses hold onto workers and by boosting the middle class.

Degree inflation

In 2014, the labor market analysis firm Burning Glass Technologies tried to capture the extent of degree inflation. The firm compared the percentage of people in a given occupation (say, executive assistant) who have a bachelor’s degree with the percentage of job listings for that occupation requiring a bachelor’s degree.

“Who you have working for you and who you want to have working for you in the future aren’t always the same,” said Burning Glass CEO Matthew Sigelman.

Sigelman found that 19 percent of current executive assistants had a bachelor’s degree, but that 65 percent of job listings for the position asked for one — a “credentials gap” of 46 percent. In surveying broader groups of occupations, Burning Glass found a credentials gap of 26 percent for management jobs, 21 percent for computer and math jobs and 13 percent for sales jobs.

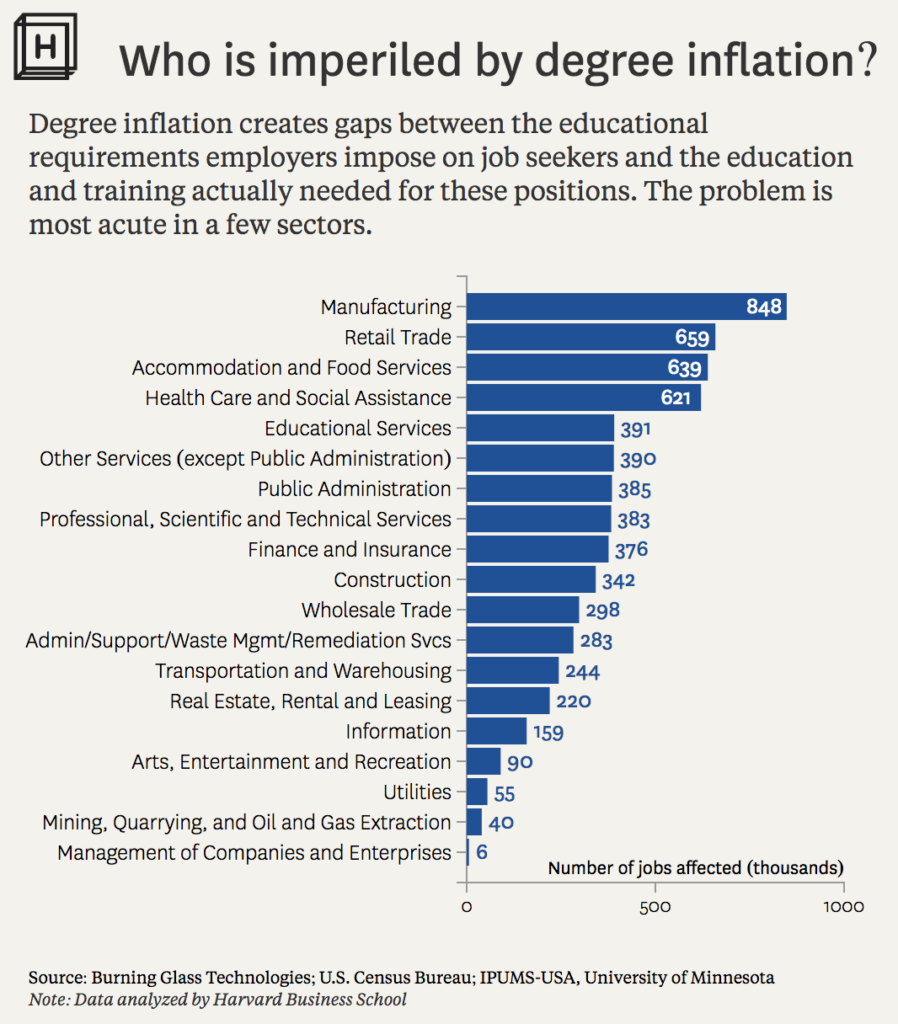

In late 2017, a research project led by the Harvard Business School, a workforce organization called Grads of Life and the consulting firm Accenture concluded in a report, “Dismissed by Degrees,” that employers “appear to be closing off their access to the two-thirds of the U.S. workforce that does not have a four-year college degree.” The researchers estimated that 6.2 million jobs were at risk of degree inflation. They cited research showing that the proportion of job listings requiring a four-year degree increased by more than 10 percentage points from 2007 to 2010.

That timespan should look familiar: The Great Recession lasted from December 2007 to June 2009. Unemployment spiked, and employers stocked up on college graduates without having to pay a premium in wages. “Some of that is legitimate, where the job is getting more technical,” said “Dismissed by Degrees” co-author Joe Fuller, a Harvard Business School professor. But employers want more than technical skills; they want characteristics like attention to detail, problem solving, working with a team. “One of the major reasons degree inflation is so common is because employers use it as proxy for those kinds of soft skills,” Fuller said.Related: Out of poverty, into the middle classUsing a four-year degree as a proxy for employability shuts out the most economically vulnerable job seekers. It hurts employers, too, Fuller and his Harvard colleague, researcher Manjari Raman, found in their report. Degree-holders command an 11 to 30 percent wage premium yet fail to justify that premium in productivity and other outcomes. It takes longer to fill jobs when filtering for four-year degrees, and degree-holders change jobs more quickly. Nonetheless, according to Harvard’s survey of 600 business and human resource leaders, 61 percent of respondents reported tossing resumes without four-year degrees, even if the applicant was qualified.

That timespan should look familiar: The Great Recession lasted from December 2007 to June 2009. Unemployment spiked, and employers stocked up on college graduates without having to pay a premium in wages. “Some of that is legitimate, where the job is getting more technical,” said “Dismissed by Degrees” co-author Joe Fuller, a Harvard Business School professor. But employers want more than technical skills; they want characteristics like attention to detail, problem solving, working with a team. “One of the major reasons degree inflation is so common is because employers use it as proxy for those kinds of soft skills,” Fuller said.Related: Out of poverty, into the middle classUsing a four-year degree as a proxy for employability shuts out the most economically vulnerable job seekers. It hurts employers, too, Fuller and his Harvard colleague, researcher Manjari Raman, found in their report. Degree-holders command an 11 to 30 percent wage premium yet fail to justify that premium in productivity and other outcomes. It takes longer to fill jobs when filtering for four-year degrees, and degree-holders change jobs more quickly. Nonetheless, according to Harvard’s survey of 600 business and human resource leaders, 61 percent of respondents reported tossing resumes without four-year degrees, even if the applicant was qualified.

That survey also revealed that 63 percent of respondents had trouble filling middle-skills jobs. Andy Van Kleunen, CEO of the National Skills Coalition, attributed that trouble to public policies that push bachelor’s degrees as a one-size-fits-all solution rather than training workers for specific middle-skill positions. The National Skills Coalition, which lobbies policymakers and employers to invest in workers’ skills, wants federal Pell Grants to be available not just for students seeking degrees but also for workers who want to take short-term courses that they could apply on the job immediately.

But part of employers’ inability to fill middle-skills jobs can be attributed to degree inflation. Fuller’s report encouraged employers to push back against the trend: “Once the logic of resisting degree inflation takes root in an organization, it soon permeates different aspects of the organization’s culture — and eventually embeds itself at the heart of its strategy,” the report states.

A ‘1-percent market’

Gina Plata and Miriam Ortiz at the offices of Just-A-Start, a workforce training organization that is helping prepare people without college degrees for middle-skill jobs in fields like medical technology. Lawrence Lanahan for The Hechinger Report

After years of being criticized for a lack of diversity, companies — especially in the technology world — are looking for ways to make their workplaces more inclusive. And a tight labor market — there were more than 7 million job openings in the U.S. as of February — has employers in many sectors scrambling for talent.

“For decades, at many companies that I worked for, I wasn’t allowed to hire unless somebody had a four-year degree,” said Trish Torizzo, the chief information officer for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. But today, she said, “supply is so low that people are almost being forced to think more creatively about how they operate.”

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt stripped the four-year degree requirement from information technology positions — including web developer — last summer, and the number of applications that made it through their initial screening doubled. To screen candidates, the company looks for a “tech stack”: a list of programming languages and tools a candidate knows.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt then revisited hiring practices for sales positions, which are heavy on soft skills, at the urging of Roberta Rainville, the vice president for talent acquisitions.

Rainville knew it was time for a change when the company found itself unable to hire a great candidate for a sales position. “They interviewed splendidly,” she said, “and then it was, ‘Well, I want to hire them,’ and I was like, ‘Yeah, you can’t.’ And they’re like, ‘Why not?’ And I’m like, ‘Because your job description says, “Bachelor’s degree required.”’ I said, ‘That’s got to go.’”

Related: Are apprenticeships the new on ramps to good jobs?

Rainville had to persuade 10 people from the sales leadership team before she could make the change. “Some folks were like: ‘We can’t take the bachelor’s degree off. We’re sending the wrong message to our teacher population that we’re selling to,’” she said. Ultimately everyone signed off, and in September the company stripped the four-year degree requirement from some of its sales jobs, and three months later did the same for software engineering jobs. Now, 11 percent of applicants who make it through the interview process for an entry-level sales position have no credential beyond a high school diploma; another 11 percent have an associate degree. Previously, all had bachelor’s degrees.

John Barros, chief of economic development for the City of Boston, introduces a panel on redefining hiring on March 28 at Wayfair headquarters in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. Wayfair is one of a growing number of companies that has opened its applicant pool to those without bachelor’s degrees. Lawrence Lanahan for The Hechinger Report

As the company retools its pipeline, it is working with organizations in Boston communities, hoping to attract job applicants it had previously failed to reach. So far, Houghton Mifflin’s relationship with Resilient Coders has resulted in the company hiring Tillman-French and another web developer. Resilient Coders’ founder David Delmar has offered to tailor part of the organization’s curriculum to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s needs.

Resilient Coders has already built a curriculum for Wayfair, a rapidly growing home furnishings company that generated $6.8 billion in revenue last year.

“A goal that we’ve set — something we think it’s reasonable to achieve in the next couple of seasons — is to have potentially as much as half of entry-level software developers come from boot camps, whereas historically it’s been 100 percent out of universities,” said Deborah Poole, Wayfair’s global head of talent acquisition.

In late March, Wayfair hosted researchers, employers and representatives of Boston’s economic development office at an event called “Untapped” to release a research report on redefining hiring in the area. The report is part of a regional effort to bring economic opportunity to Bostonians who lack a four-year degree — more than 50 percent of adults in the city. “There is a huge amount of talent in this market that we are not talking to,” Poole said.

When the time came for audience questions, the first to speak up was Delmar from Resilient Coders. He asked a panel including city leaders, researchers and executives a question that was met with silence followed by nervous laughter: “Is it time — will it ever be time — to ban the B.A. requirement from coding jobs?”

Closing the gap

Rouguiatou Diallo and Stephanie Castaños of Resilient Coders, a boot camp that trains people of color for web development and software engineering jobs. Lawrence Lanahan for The Hechinger Report

With more than 20 four-year colleges and universities, Boston is known as “America’s college town.” But only 25 percent of the city’s black and Latino adults have a bachelor’s degree, and the Boston metro area ranks sixth in the nation for income inequality. The regional economy might be thriving, but many of its jobs are taken by people who come from outside Massachusetts. When it comes to the labor market, said Marybeth Campbell, executive director of Skillworks, a workforce group dedicated to low-income, low-skilled Bostonians, “our two-year community colleges are competing with our four-year schools, and those four-year schools are competing with three or four schools here: Harvard, MIT.”

The staff at Resilient Coders sees this racial and economic inequality up close. “If you’re looking for someone, you’re going to use your networks,” said Rouguiatou Diallo, chief of staff at Resilient Coders. “In a segregated America, your networks are going to be looking the same as you, most of the time.” The four-year degree requirement is a habit, Diallo said, but habits change. “So what if it becomes a habit that one of your pipelines is a boot camp program?”

Faisal Africawala, 29, a Cambridge resident who emigrated from India in 2010, worked for years at 7-Eleven convenience stores and a Whole Foods Market, making $8.50 to $11 per hour. In 2018, he entered a free nine-month program at a workforce organization called Just-A-Start, training for the biomedical industry. Halfway through the program, a pharmaceutical manufacturer in the Boston suburbs hired him as a manufacturing technician on the second shift. He wears protective gowns and fills vials with medicine in sterile rooms, and is checked for microbes every time he goes through the door. Africawala said he earns $19.26 per hour and gets health insurance, life insurance and a retirement plan.

Rouguiatou Diallo and Stephanie Castaños of Resilient Coders, a boot camp that trains people of color for web development and software engineering jobs. Lawrence Lanahan for The Hechinger Report

“I’m already looking to buy a house, which I never thought I would even have,” said Africawala, who takes what overtime he can get. “It’s only been six months, but I’ve managed to save ten thousand bucks.”

In a survey of its alumni dating to 2004, Just-A-Start said the 143 respondents indicated that they have seen an average salary increase of $14,778 per year compared to their previous jobs. The program reaches out to employers and encourages them to consider candidates who don’t have four-year degrees, said Gina Plata, Just-A-Start’s director of education and training.

Related: Test prep to get into vocational education? Yup, it’s a thing

Newer programs have harnessed technology to draw employers’ attention to job candidates’ skills rather than their degrees. After coming across eye-tracking research showing that recruiters spend an average of just seven seconds skimming a resume, Grads of Life developed the “7 Second Resume,” a video in which job seekers highlight one skill they can bring to a job. The developers of the job-listing portal Skillist encourage users to highlight their skills rather than degrees, and they persuade employers to shape their listings around skills. Wayfair and about 10 other employers have signed on.

New research shows that employers are recognizing that degree inflation can work against their interests, preventing them from finding the workers they need. Economist Alicia Sasser Modestino, an associate professor at Northeastern University, and two colleagues found that employers loosened educational requirements when the economy recovered following the Great Recession: From 2010 to 2014, the proportion of listings asking for a four-year degree dipped a quarter of a percentage point for every 1 percent drop in a region’s unemployment rate.

Ryan Tillman-French rides the Mattapan Trolley on his commute to work at the Boston office of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. The publishing company recently stopped requiring job applicants to hold a bachelor’s degree, opening the door for workers like Tillman-French, who has training in coding and a two-year degree. Lawrence Lanahan for The Hechinger Report

That raises a troubling question: If employers turn to skill-based hiring during a tight labor market, will they start hiring based on four-year degrees again during the next economic downturn?

“That’s the question that keeps me up at night,” Grads of Life principal Elyse Rosenblum said with a chuckle, “and why we are working so hard and so fast to try to instill these practices.”

The other lingering question is whether nondegree hires will stay and advance at their workplaces. “That is absolutely critical,” Rosenblum said.

The future is always on Ryan Tillman-French’s mind — both his own future and that of the community that raised him. He’s collecting backpacks to give out to children in his old Detroit neighborhood, and eventually, he wants to buy a house there, even if he doesn’t move back right away. One day, he’d like to run his own company.

In the meantime, Tillman-French believes there’s a path for advancement at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. He already makes $65,000 a year, a rebuke to a culture and an economy that exalts a bachelor’s degree as the gold standard for upward mobility while young adults stagger under the weight of the nation’s record $1.5 trillion in outstanding student loan debt.

“My success is truly determined by me,” Tillman-French said. “How much work I put into this is how much success I’m going to get.”

This story about jobs without a college degree was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter.