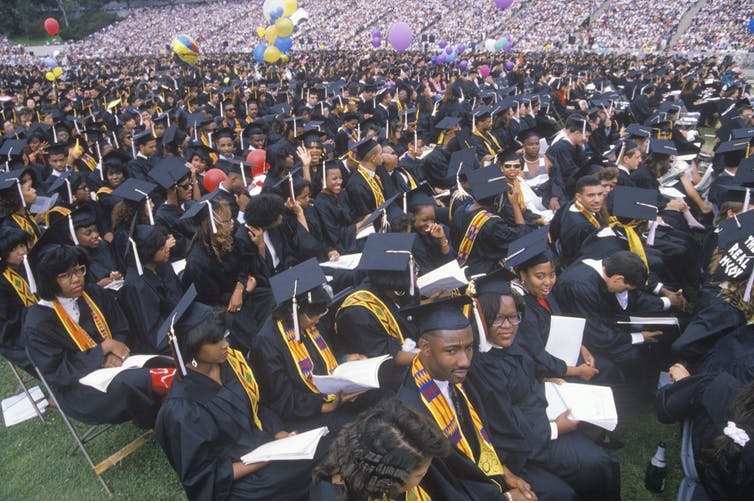

Just under half of all Pell Grant recipients graduate on time, new data show. Joseph Sohm/www.shutterstock.com

As college students nationwide prepare for graduation, a new analysis has shown that just under half of all those who receive Pell Grants – the federal government’s main form of direct financial aid for low-income students – finish their four-year degree programs on time.

The federal government considers “on time” being six years for a four-year degree. The maximum federal Pell Grant program award for the current school year is US$5,920. Next school year, the award will rise to $6,095.

So, why are so many low-income college students not completing their degrees within this time frame? The question is an important one because last year the federal government spent $26.9 billion dollars on Pell Grants. It’s also important because Pell Grant recipients can expect to earn substantially higher salaries if they complete their degrees.

Speaking as a researcher who focuses on issues of performance at public institutions, the available data suggest the reason Pell Grant recipients have lower graduation rates is related to both the nature of the colleges these students attend, as well as the personal barriers these students face.

Compared to other college students, those receiving Pell Grants are more likely to belong to a racial minority, to have parents who never went to college, and to be parents themselves.

Personal barriers to success

As a result of their backgrounds, Pell Grant students – like other low-income students – tend to face many unique personal barriers to completing a college degree, such as being a single parent or not going straight to college out of high school.

Completing a degree is more difficult for students who are parenting children, especially for single parents. With less support available from parents and other family members, Pell Grant students can feel a strong pull to pause their studies and start working, especially if they encounter unexpected expenses, such as significant medical bills or car repairs.

Pell Grant students are often less academically prepared for college than their peers. For example, Pell Grant students tend to have lower SAT/ACT scores and graduate from high schools that don’t offer a rigorous curriculum. This is unsurprising given that academic success in K-12 education systems in the U.S. is highly correlated with income and race.

Also, since research suggests that family members who have gone through college are often an important source of information about how to succeed in college, those who are first-generation college students miss out on a significant source of motivation and advice.

College quality

The new analysis – which comes from a center-left think tank called Third Way – shows that most four-year colleges have lower graduation rates for Pell Grant students than for students not receiving Pell Grants. But as the published data from the analysis also shows, Pell Grant students also tend to go to schools with lower overall graduation rates.

Many colleges in the U.S. have very low graduation rates. Nationwide, only 59 percent of students who enroll full time in a bachelor’s degree program complete their degree within six years, although the Third Way report’s data indicate that figure rises to 67 percent if Pell Grant students are excluded from the calculation.

The top schools in a given state typically have much higher graduation rates. These top schools are generally admitting highly qualified students, who are the most likely ones to complete a degree anyway. But studies suggest college quality also plays a role in determining the likelihood that a student will finish their degree.

Lower-quality schools often have fewer financial resources, which makes it harder for them to offer students support in the form of advising, tutoring or small classes.

Given lower levels of academic preparation, students eligible for Pell Grants likely find it harder to be admitted to the highest-quality colleges in the country. This matters because attendance at a quality college could boost their chances of graduating on time. Low-income students may also face a greater need to attend a college near their hometown, particularly if they wish to save money on living expenses by living with family. Some students who are geographically constrained will lack having any high-quality colleges in their area.

Potential solutions

What can be done to improve graduation rates for low-income college students?

The evidence suggests that increased support for students may help. For instance, a recent analysis of a random control trial at a community college found that low-income students who received access to emergency financial assistance – in combination with a case manager – were much more likely to complete an associate’s degree.

![]() Another recent study found evidence that more students complete degrees when colleges have more funding.

Another recent study found evidence that more students complete degrees when colleges have more funding.

Nathan Favero, Assistant Professor of Public Administration & Policy, American University School of Public Affairs

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.