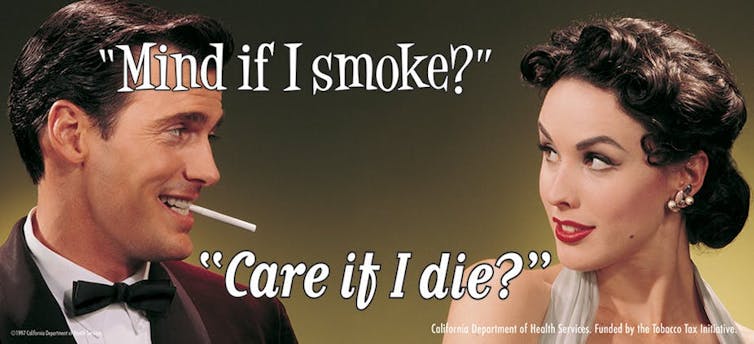

Anti-smoking ads such as this one can help curb smoking, but studies are suggesting that raising the tax on cigarettes may be most effective to help deter poor people. California Department of Public Health, CC BY-SA

Robert McMillen |November 1, 2018

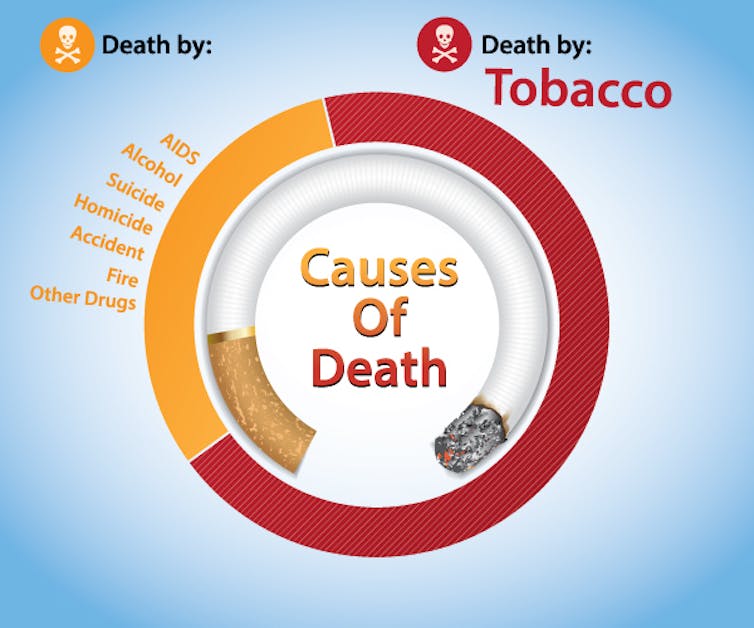

Lung cancer is the biggest cancer killer in the country, and almost 90 percent of deaths from this disease are directly attributable to cigarette smoking. Many cancers, such as breast cancer, that were once a death sentence are now treatable, yet lung cancer survival rates remain below 20 percent. A cure may be elusive, but the medical community can stop this disease and eliminate most future lung cancer deaths.

Most lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking, and smoking is a socially influenced behavior. People tend to catch it from tobacco marketing and by modeling smokers. Tobacco companies spend more than a million dollars an hour to market their products in order to recruit new smokers.

I am a tobacco control researcher who has studied ways to stop the disease. There is a vaccine to smoking, and you don’t even have to get a shot. Scientists have more than 60 years of research on how to get people to quit smoking and prevent teens from starting to smoke. Evidence compiled over many years shows that a combination of hard-hitting media prevention campaigns, strict laws and higher taxes can reduce the numbers of teens who start smoking and nudge adults smokers toward quitting.

Smoking rates drop by more than half

Cigarettes were a common part of American life for most of the 20th century. Smoking peaked mid century; more than 40 percent of Americans smoked cigarettes in 1965.

The prior year, the surgeon general’s warning about the dangers of smoking launched a massive effort to end smoking. Media campaigns about the newly established dangers of smoking led to the first sustained dip in smoking prevalence in the United States. Subsequent smoke-free policies beginning in the 1980s, age restrictions and other regulatory constraints on smoking and the tobacco industry led to further declines in smoking. Today fewer than 15 percent of adults are smokers.

And yet, while fewer and fewer Americans smoke, smoking rates remain persistently high among poorer Americans. Most families with higher socioeconomic status live, work and play in places where smoking is not allowed and in fact frowned upon.

The social climate around tobacco is very different for poorer Americans. More of their friends and family smoke, and many live and work in places where indoor smoking is allowed.

Reducing the smoking rate by more than 50 percent is one of the great public health successes of the past hundred years, but poorer Americans were left behind. Broader implementation of effective tobacco prevention strategies could reduce lung cancer in this population, studies suggest.

Telling kids the costs, and the truth

Studies show that one of the first steps in reducing smoking is to change the way that people think about tobacco. Successful media campaigns must go beyond simply warning about the health risks of smoking. Campaigns should provide youth with new information that reframes the images of smoking portrayed in tobacco ads. One recent national campaign to prevent youth smoking demonstrates this strategy.

Launched in 2014 by the FDA, “The Real Cost” campaign reframes smoking. Rather than glamorized images of smoking, youth learn that every cigarette costs them something. These costs include the cosmetic damage of smoking, loss of control due to addiction, and the chemistry set of toxicity in cigarette smoke. Longitudinal surveys that followed youth over four surveys administered from 2013 to 2016 revealed that this campaign prevented approximately 350,000 youths from starting to smoke between 2014 and 2016.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, and it also accounts for close to 1 in 5 deaths. SunnySideUp/Shutterstock.com

Media campaigns can reframe the way people think about smoking and quitting smoking, but they do not directly compel people to quit smoking or not to start to smoke. Laws and policies such as no smoking in restaurants provide a booster to these media campaigns. By constraining the behavior of tobacco companies, retailers and smokers, regulatory action strongly nudges smokers toward quitting and youth away from smoking.

And, while regulatory actions restrict individual and commercial freedoms, most Americans support policies to prevent smoking. Secondhand smoke harms nonsmokers and smoking costs all of us billions of dollar in health care. The benefits of less smoking outweigh any perceptions of regulatory burden. Moreover, these actions are low to no cost to implement, and tobacco taxes actually generate revenue.

Starting in the 1990s, cities and states began banning smoking in offices restaurants to protect nonsmokers. These policies also changed the social climate impacting people’s decisions about tobacco use. Teens who were experimenting with tobacco and smokers began to get the message that most people do not smoke and do not find it acceptable. Fewer teens started smoking and more adults quit smoking in the wake of these smoke free policies.

Although tobacco companies resist these smoking bans, these policies are popular with Republican and Democratic voters. In recent years, smoking bans have extended to private venues. Several states ban smoking in cars if there is a child present, while landlords and property associations frequently ban smoking in private residences. And this year, the federal government banned smoking inside of apartments managed by the Housing and Urban Development Authority (however, this policy does not apply to Section 8 housing).

Taxation without misrepresentation

A rally in Helena, Montana, in August 2018, to garner support for an increase in the tobacco tax in Montana. Matt Volz/AP Photo

Beyond restricting where people can smoke, many cities and states prohibit the sale of tobacco products to people under 21. The social circles of most high school students do not include 21-year-olds, so these teens are unlikely to have friends who can legally buy cigarettes. Needham, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, was the first city to raise the age to 21, and teen smoking decreased compared to neighboring suburbs. Preliminary evidence from California indicates that this policy is limiting teens’ ability to buy cigarettes.

Taxes on tobacco are popular with many voters, and represent a win-win for lawmakers. With higher prices, people buy fewer cigarettes and the higher taxes generate more revenue. This new revenue could provide support for quit attempts and fund programs to prevent teens from becoming smokers. The District of Columbia recently enacted a $2 a pack tax increase on cigarettes, and voters in Montana and South Dakota will vote Nov. 6 on whether to increase tobacco taxes in their states.

Lung cancer remains a deadly disease, but our country has the vaccine to prevent this disease. Informed by more than 60 years of research on effective hard-hitting media campaigns and regulatory policies, lawmakers have the tools to eliminate most lung cancers. Studies suggest that wider implementation of these policies, especially in places with more poverty, would reduce smoking and prevent lung cancer. Quitting smoking is hard, but these popular evidence-based strategies can help.![]()

Robert McMillen, Professor & Associate Director of the Social Science Research Center, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.