Facebook recently disabled some ads on its site making dubious claims about Truvada. Tony Webster/CC BY-SA 2.0

Some ads can be more than misleading – they can put your health at risk.

Last year, ads paid for by law firms and legal referral companies started cropping up on Facebook. Typically, they linked Truvada and other HIV-prevention drugs with severe bone and kidney damage.

But like a lawsuit, these assertions do not always reflect the consensus of the medical community. They also do not take into account the benefit of the drug or how often the side effects occur.

On Dec. 30, Facebook said it disabled some of the ads after more than 50 LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS groups signed an open letter to Facebook condemning them for “scaring away at-risk HIV negative people from the leading drug that blocks HIV infections.”

Based on our research involving televised drug injury ads, advocacy groups are right to raise the alarm about how these ads might affect important health decisions.

Although drug injury ads are selling legal services, that’s rarely obvious, making it harder for consumers to invoke their usual skepticism toward medical information from lawyers.

Here are a few deceptive tactics we noticed in the Facebook Truvada ads, which you can also spot in drug injury advertisements more broadly.

Ads in disguise

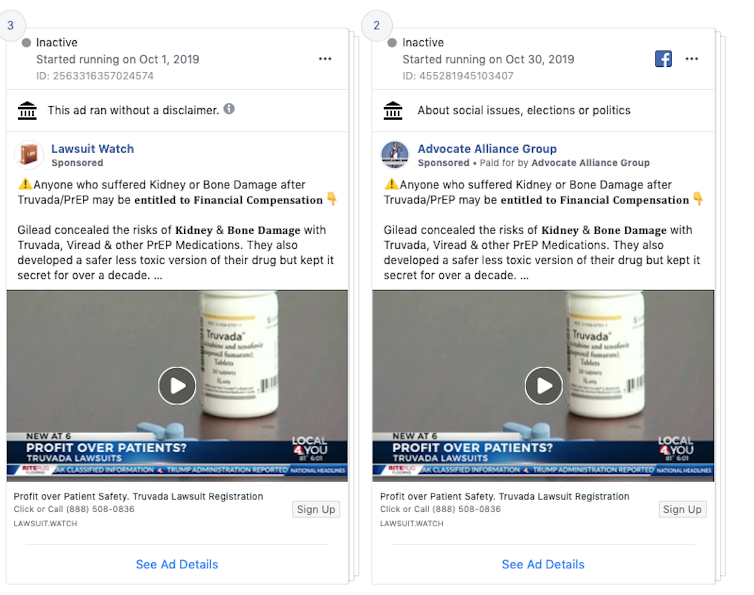

Advertisements in this genre sometimes masquerade as other types of content, like public service announcements or local news. For example, a series of identical Truvada-related ads sponsored by “Lawsuit Watch” and “Advocate Alliance Group” prominently featured video from a local news story.

This clever but ultimately misleading tactic is known within the marketing literature as an “Omega strategy,” in which the advertiser tries to “redefine the sales interaction” to disguise its pitch. It’s like when insurance companies offer to “assess your personal risk,” when they’re really just trying to sell you insurance.

An example of Facebook ads about HIV-prevention drug Truvada. Screenshot by author of Facebook ad bank

Similarly, these legal advertisers appear to be educating patients but their true goal is to sign you up for a lawsuit – and most likely sell your name to a lawyer looking for clients.

What makes the ad even more complex to process is that embeds actual local news footage, which mostly consists of reporting allegations from a lawsuit.

By using news broadcasters to deliver their claims, the advertiser enhances the message’s credibility, which makes it less likely that consumers will critically analyze the content.

Who sponsored this?

Drug injury ads can also mislead when the sponsors are not clearly identifiable as for-profit legal referral businesses.

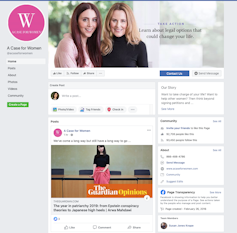

For example, some Truvada-related ads that Facebook removed were sponsored by “A Case for Women,” whose name suggests an advocacy organization. The Facebook page for this entity does little to clear up this misapprehension. It’s only when you track down its website that you get a whiff of legalese, with references to a “free consult” and the advice to “take action (legal or otherwise)” for “life-changing financial compensation.” Even then, the information is presented in the name of “Women Empowerment,” along with inspirational pictures and blog posts.

The same kind of confusion can arise from ad sponsors with names like “Lawsuit Watch” and “Advocate Alliance Group.”

It’s not obvious that this ad sponsor is a legal referral agency soliciting consumers to sue drug manufacturers. Facebook ad bank

Consumers are misled when advertisers do not clearly disclose their status as law firms or for-profit legal referral businesses. In one experiment for a study published last year, we showed consumers different versions of drug injury TV ads. Around 25% of consumers did not recognize drug injury advertising as such when the sponsor was not clearly revealed, compared with 15% when an attorney was prominently featured. By contrast, only 2% of consumers misidentified the source of a pharmaceutical ad.

This confusion appears to alter how consumers process information found in the ads. Those who were shown the more deceptive drug injury ad perceived the featured drug to be riskier, expressed a greater reluctance to take the drug and were more likely to question their doctor about the medication.

When you’re dealing with medication that prevents a life-threatening virus like HIV, transparency is essential.

Attention-getting claims

Drug injury advertisements also commonly include stark language and imagery like “consumer alert,” “medical alert” or “warning.” This language is used to capture a viewer’s attention. We have found that drug injury advertisements with more graphic descriptions of side effects inflate perceptions of risk.

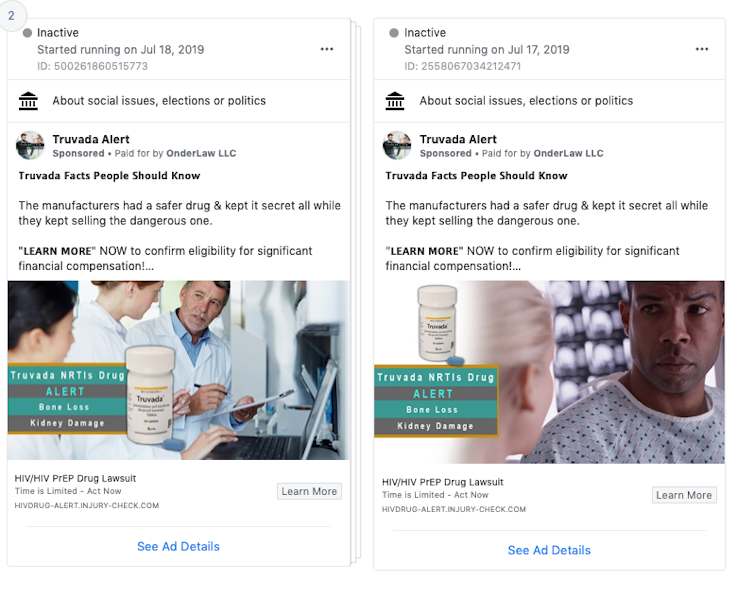

These ads characterize Truvada as dangerous. Facebook ad bank

Language of this sort can be found in the Facebook ads about Truvada. Some ads are framed as a “Truvada NRTIs Drug Alert,” claiming that “the manufacturers had a safer drug & kept it secret all while they kept selling the dangerous one.”

But as the authors of the open letter to Facebook point out, characterizing this particular drug as unsafe is not accurate, particularly when compared with the obvious harm of HIV infection.

Moreover, framing ads in this way is not necessary. Advertisers could instead state they are looking for individuals who have experienced the listed side effects without portraying the ad as an “alert” that the drug is “dangerous.”

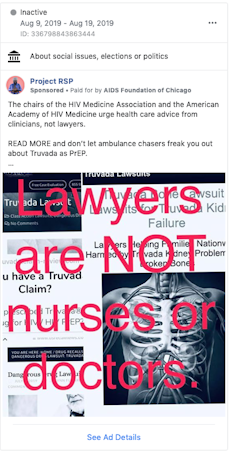

The AIDS Foundation of Chicago sponsored advertising to counteract legal solicitation ads. Facebook ad bank

Better regulation

These types of ads have been almost entirely unregulated until recently.

The Federal Trade Commission, which regulates advertising, declined to act for many years. But in September, the agency issued a letter to seven law firms and legal referral companies warning them that their advertising is deceptive, suggesting it may be finally changing its tune.

And although states regulate legal advertising through attorney ethics rules, our past research found no examples in which a lawyer was disciplined for misleading drug injury ads.

The last line of defense, then, is Facebook itself, through its ad policies. Beyond blocking misleading ads, our research suggests that clear disclaimers can help to reduce – but not eliminate – consumer confusion.

Ultimately, it’s up to federal and state regulators to treat drug injury advertisements as a matter of public health and require advertisers to present medical information in a way that helps, rather than misleads, consumers.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter. ]Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Oregon and Jesse King, Assistant Professor of Marketing Weber State University, Weber State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

January 4, 2020