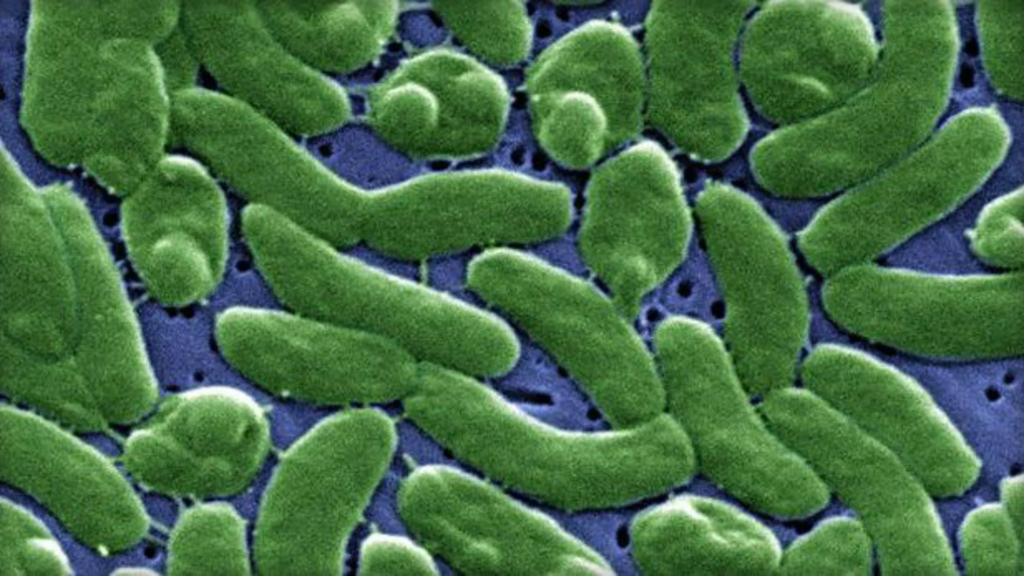

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention detected more than 220 cases last year of a rare breed of “nightmare bacteria” that are virtually untreatable and capable of spreading genes that make them impervious to most antibiotics, according to a report released Tuesday.

Although the CDC has warned of the danger of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for years, the new report helps illustrate the scope of the problem. Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC’s principal deputy director, said she was surprised by the extent of the spread.

“As fast as we have run to slow [antibiotic] resistance, some germs have outpaced us,” Schuchat said. “We need to do more and we need to do it faster and earlier.”

The CDC set up a nationwide lab network in 2016 to help hospitals quickly diagnose these infections and stop them from spreading.

One in 4 germ samples sent to the lab network had special genes that allow them to spread their resistance to other germs, the CDC said. In 1 in 10 cases, people infected with these germs spread the disease to apparently healthy people in the hospital — such as patients, doctors or nurses — who in turn can act as silent carriers of illness, infecting others even if they don’t become sick.

Nightmare bacteria — those that are resistant to almost every drug — are particularly deadly in the elderly and people with chronic illnesses. Up to half of the resulting infections prove fatal, Schuchat said.

While those bacteria are terrifying on their own, the “unusual” genes discussed in this report are truly the “worst of the worst,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. About 2 million Americans are sickened by antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year and 23,000 die, according to the CDC.

“There are certain bacterial genes that are more worrisome than others, that are much harder to treat,” Adalja said. “These genes are lurking in American patients and they are spreading in hospitals and health care facilities.”

Many researchers have worried about the emergence of a “post-antibiotic era,” in which patients succumb to once-treatable infections. Antibiotics don’t just save lives when people develop infectious diseases such as pneumonia. They are also the “safety net” for patients undergoing surgery and cancer treatment, Schuchat said.

Dr. Michael Osterholm compared the problem to a “slow-moving tsunami.”

“This isn’t an acute crisis where a wave just hits you,” said Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. “But we see these rare cases of resistance in remote areas of the world, and within a year or two, it’s everywhere.”

As alarming as the new numbers are, Schuchat said there is good news to report.

Studies show that aggressive hospital action can limit the spread of outbreaks.

In one case, the CDC network helped diagnose bacteria carrying resistance genes in an Iowa nursing home resident with a urinary tract infection. Public health staff tested 30 other nursing home residents and found five were infected.

Aggressive measures, such as wearing gowns and gloves while caring for infected patients, prevented anyone else from becoming sick, Schuchat said.

Aggressively diagnosing and containing such infections can reduce infections by 76 percent, the CDC said.

Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and health policy disease at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, said the CDC’s efforts to contain and slow the spread of nightmare bacteria seem to be working.

The CDC lab “network is working at an absolutely high level of effectiveness,” Schaffner said. “It’s identifying problems with great precision and initiating the appropriate response with the local health department and hospital staff.

“That’s the ‘good news spin’ bun around a scary hot dog,” Schaffner said.

Maintaining these labs is vital, said Dr. Paul Auwaerter, president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Containing antibiotic resistance “is vital to maintaining the strides made in many areas of modern medicine,” Auwaerter said.

Osterholm said world leaders need to do far more to prevent antibiotic resistance.

A 2016 report commissioned by the British government and Wellcome Trust called for investing $40 billion over the next decade to fight the problem. About 700,000 people around the world die due to antibiotic resistance each year. Without immediate action, annual deaths could rise to 10 million by 2050, according to the report.

Bacteria naturally evolve to resist drugs used against them. The more the drugs are used, the faster this happens, Osterholm said.

While developing new antibiotics can help, Osterholm compared that approach to “trying to dig yourself out of a hole.”

It’s far more important that countries around the world use antibiotics more judiciously, Osterholm said. Doctors today often prescribe antibiotics when they’re not needed.

In developing nations, patients often buy antibiotics on the street, Osterholm said, noting that antibiotics are also widely used in agriculture.

Vaccines can also help fight antibiotic resistance, he said, by preventing people from ever becoming sick and needing antibiotics.

By Liz Szabo, Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.