Carolin Schellhorn | Oct 8, 2018

The latest employment data, released on Oct. 5, point to a persistent economic puzzle: The unemployment rate is the lowest in nearly half a century yet wages have been very slow to react.

In the past, such low unemployment levels have driven up wages. Yet, apart from a relatively recent acceleration, real wages have barely budged since the Great Recession and in fact are little changed from the 1980s.

This puzzle can be even more confounding when you consider some of the biggest American companies have been boosting the minimum wages they pay their employees to levels way above the federal minimum of US$7.25 an hour. Amazon became the latest this month, promising to pay all workers no less than $15 an hour, following similar raises for employees of Costco, Walmart, Target and others.

I believe there’s good reason to be skeptical that these sporadic pay hikes will solve the problem of stagnant wages. In fact, it is the rise of such superstar companies as Amazon that has contributed to the problem in the first place.

Stagnant wages

Wages typically need to rise 3.5 to 4 percent a year following an economic recession in order to help workers recoup their losses from the downturn.

But average hourly earnings growth for private sector nonfarm workers has been significantly below that, and most of the gains have been wiped out by inflation.

As a result, workers are getting an ever-shrinking share of U.S. national income, which declined from about 65 percent in the 1960s to as low as 56 percent in 2014.

Everything from robots and global competition to the erosion of unions has been blamed. While there’s certainly truth to each explanation, a new one has been gaining traction: superstar companies.

Superstars rise

Amazon, Google, Uber, Federal Express and a few other exceptional companies have gobbled up an increasing share of their industry’s markets to a point where small companies just can’t compete.

In retail, for example, the top four companies controlled 30 percent of sales in 2012, up from 15 percent in 1982. In finance, the share rose to 35 percent from 24 percent. And in the service sector, it climbed to 15 percent from about 10 percent.

The industry concentration, along with inexpensive loans engineered by the Federal Reserve’s ultra-low interest rate policy, has allowed a select few companies to make significant investments in productive technologies, such as in artificial intelligence and automation. This has helped them increase their market shares even further. And in turn, this is what is making it easier for these companies to lift wages, whether by setting higher minimum wage floors for their workers or simply paying more across the board.

While that’s all fine and good, the problem is that more than half of American workers in the private sector are employed by companies with fewer than 500 employees. These small businesses have suffered as a result of the superstars’ growing dominance and also can’t take advantage of the record-low borrowing costs because they do not have access to the stock and bond markets.

Because small- and mid-size employers do most of the hiring in the U.S., it is their wages that dominate the industry standards. And they are having a hard time increasing pay for their workers.

The rise of superstar companies is also what is driving widening income inequality today. While we usually think about inequality in terms of the gap between higher and low earners, researchers have found that the bigger issue is the gap between rich and poor companies, which in turn reinforces the gap in pay between individuals.

It is a good thing that the likes of Amazon are setting a much higher floor under their workers’ wages, but the slimmer profit margins at their smaller rivals make it virtually impossible for them to do the same. This will cement the superstars’ market power even further.

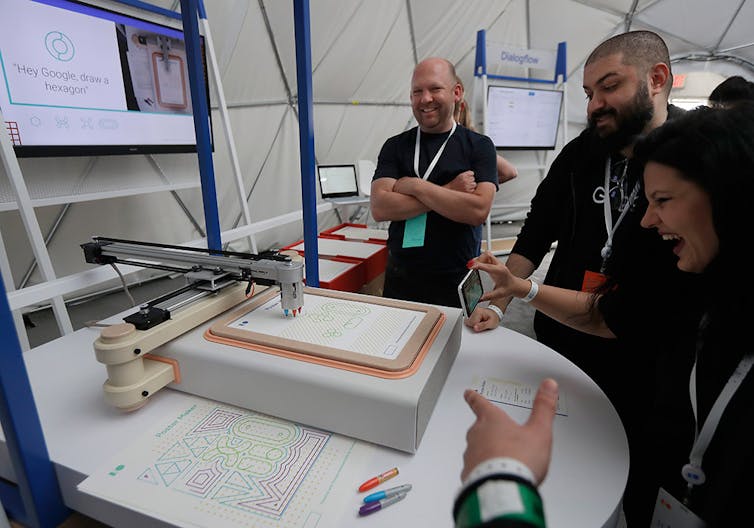

Superstar companies like Google have been able to make significant investments in productive technologies like AI. AP Photo/Jeff Chiu

An incentive to act

Fortunately, superstar companies have an incentive to do something about this because a situation in which wage growth is below par is bad for business as well as for the workers.

That’s because low wages threaten the physical and mental health of a large swath of the workforce as increasing numbers of workers can’t afford to invest in good food, preventative health care, continuing education and skills training. And in a vibrant economy, workers must stay healthy and educated to remain productive. Besides, low wages also reduce consumption and economic growth.

As such, stagnant wages are one of the main reasons overall U.S. productivity growth has also been sluggish in recent years and declining toward zero. This is very bad for the U.S. economy and companies, both large and small, since high rates of productivity are vital to a country’s long-term growth rates – and to higher wages as well.

The solution is in thinking about worker productivity as a collective resource. Companies certainly have an incentive to keep labor costs low, but they also have a strong incentive to ensure, collectively, that worker productivity grows over time.

The trickier part is getting a bunch of hotshot companies to act in concert to solve a problem they all suffer from. It’s basically a “tragedy of the commons” scenario in which a shared resource is spoiled because participants’ self-interest causes them to behave against the common good.

But political economist Elinor Ostrom has shown – in research that won her a Nobel – that organizations, communities and other stakeholders have frequently found ways to govern the “commons” without tragedy.

My own soon-to-be-published research is on how groups of companies can organize themselves to preserve shared resources. The Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, for example, is collaborating with some companies like Unilever and JPMorgan Chase to engage in collective action on climate change.

So while I applaud that Amazon and others are lifting their own employees’ pay, the problem they’re trying to solve will remain until the majority of the workforce gets a raise too.![]()

Carolin Schellhorn, Assistant Professor of Finance, St. Joseph’s University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.